Not sure what happened in our conflict areas in January and February? Get up to speed!

Great Lakes of Africa: Democratic Republic of Congo

Lindah Mogeni

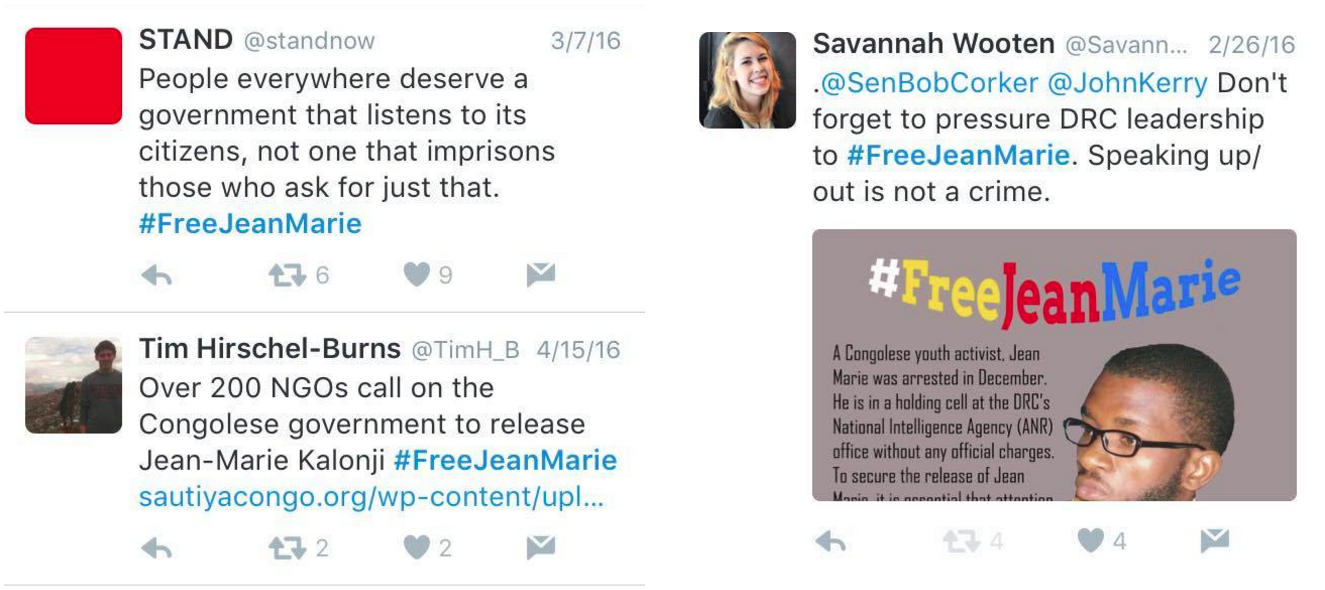

The United Nations Joint Human Rights Office (UNJHRO) has documented more than 400 cases of human rights violations, including at least 52 arrests, in the DRC since early 2016. Jose Maria Aranaz, the head of UNJHRO, affirmed that this year’s rights violations “exceeded the number [of violations] during the January protests of last year.”

On February 10, the United States Special Envoy to the Great Lakes Region, Ambassador Thomas Perriello, cautioned the US Congress of a brewing political crisis in the DRC, particularly should President Joseph Kabila fail to surrender power in the upcoming November elections in adherence to the constitutional provision that mandates a two-term presidency limit. Addressing the same Senate committee, Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, emphasized the “potentially disastrous results” that could arise from election-related political upheaval for both DRC citizens and those throughout the region.

A Human Rights Watch report revealed that 8 youth activists were arrested and detained by authorities on February 16 along with an estimated 30 political opposition supporters for participating in a peaceful protest against delayed elections held in conjunction with a national strike dubbed by the Congolese people as ville morte – meaning ‘dead city’ in French. The ‘dead city’ protests were most prevalent in Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, Goma, and Bukavu.

As aptly highlighted by STAND’s Timmy Hirschel-Burns, the date of the ville morte protests, February 16, holds significant symbolism for the Congolese people. On this day in 1992, scores of church members protested against then-president Mobutu Sese Seko’s cling to power. These protests contributed to the fall of Mobutu’s regime. Now, many Congolese are similarly protesting President Kabila’s unconstitutional efforts to remain in power. Hirschel-Burns writes that the push for Kabila to step down from power makes these protests “a powerful historical analogy.”

The arbitrary arrests are among a series of threats and clampdown efforts by Kabila’s government that have occurred since October of last year. His government has repeatedly attempted to thwart opposition supporters and protesters who are speaking out about the upcoming November elections. Notably, key parliamentarian and opposition leader Martin Fayulu was arrested and detained on February 14 for his organizational role in the ville morte protests. He was released after seven hours without charges. Several ville morte protesters also reported receiving anonymous threatening text messages.

Student representatives and leaders from STAND, The Enough Project, and Jewish World Watch have signed a joint letter to Secretary Kerry and other U.S. officials calling for attention to these arrests and for more vocal support for democratic processes within the Congo.

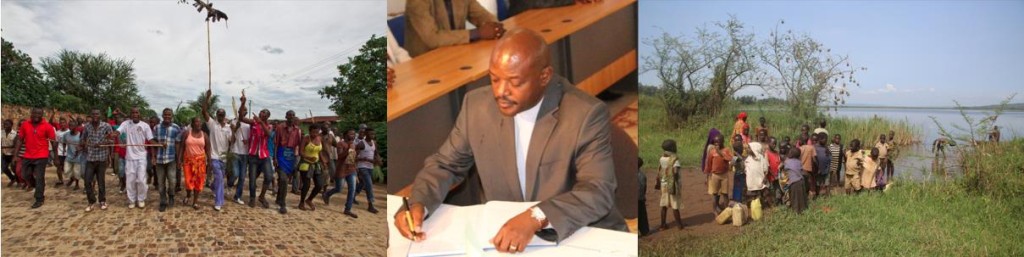

Great Lakes of Africa: Burundi

Lindah Mogeni

On their February trip to the Great Lakes region, Ambassador Tom Perriello and Assistant Secretary Thomas-Greenfield warned that the destabilization of Burundi serves as a foreboding example of what results when a “leader clings to power while ignoring binding commitments to step down.”

Ms. Thomas-Greenfield additionally expressed concern over Burundi’s internal peace prospects, iterating not only that they did “not appear promising,” but that the talks “are being held in an environment characterized by fear, repression, and lack of freedom of expression.” In agreement with this assessment, the State Department’s top Africa diplomat conveyed that not much is expected from the internal dialogue between the Burundian government and some of its opposition members, stating that it “lacks credibility, funding and externally-based opposition members.” This is significant because many opposition members and independent journalists have left the country in recent months.

Despite the lack of enthusiasm regarding the Burundi talks, the African Union has favored deploying peacekeeping troops to Burundi. According to an African Union statement, a delegation of five heads of state arranged to consult with President Nkurunziza regarding a potential deployment. The deployment of a peacekeeping force would be a large step for the country, especially in the wake of alleged “credible reports” received by Ambassador Perriello claiming that Burundian refugees in Rwanda have been recruited by groups seeking an armed overthrow of President Pierre Nkurunziza. The Rwandan government has since promised to investigate the reports and has made vocal commitments to relocating Burundian refugees to third countries.

Reports by Human Rights Watch reveal that President Nkurunziza’s government-backed forces and authorities have shown “increased brutality” in their efforts to thwart perceived opponents and that summary executions, abductions, torture, and arbitrary arrests are occurring at alarming rates. Bujumbura is currently witnessing “new levels of lawlessness.”

Rather than dead bodies littering the city streets, a common daily sight in late 2015, “many abuses are now taking place under the radar, with security forces secretly taking people away and refusing to account for them.” While in Bujumbura, Human Rights Watch employees attempted to meet with Burundian government officials but received no response.

South Sudan

Jason Qu

At the end of January, South Sudan missed a deadline to form the long-awaited South Sudanese unity government due to President Salva Kiir’s controversial order to proceed with the formation of 28 new states, dissolving the original 10 states that made up the country. This order was questioned by opposition figures and external parties who viewed it as an obstructive decree with the potential to break down the peace agreement and send the country back into civil war. However, the Dinka Council, Kiir’s supporters, and the South Sudanese Army offered their support for the plan, considering it a provision which would give localities more power over social services. The Jieng Council warned that war could resurface if Kiir’s order was reversed. Tensions rose dramatically due to the creation of these new states, as the shift divided states on tribal lines, frustrating many ethnic groups.

Clashes in Western Equatoria between the Arrow Boy militias, a series of groups that began operating in the region as a “self-defense” force, and the SPLA killed five people. Clashes like these have contributed to the declining humanitarian situation in South Sudan – with the UN making an appeal for 1.3 billion dollars in funding for aid in South Sudan and the number of people sleeping on UNMISS bases topping 200,000.

On February 12 of this year, South Sudanese President Salva Kiir appointed SPLM-IO leader Riek Machar, his chief political rival, the position of Vice President of South Sudan, urging him to return to the capital within 7 days to begin forming a new government. From South Sudan’s independence in 2011, Machar occupied the position of Vice President until the most recent civil war, at which point he fled from Juba in July 2013. Vice President James Wani Igga was sworn in as 2nd Vice President on August 23,2013. Machar accepted the appointment but stated he will only return to Juba and begin his duties as Vice President when the capital is fully demilitarized, as stipulated in the 2015 August Peace Accords. Juba issued an order on the day of Machar’s appointment to withdraw SPLA forces from the capital by the end of February. Kiir did not immediately react to Machar’s demands. The SPLA indicated the demilitarization would be completed by the end of February.

In mid-February, opposition forces claimed that the SPLA launched offensives against rebel forces in Upper Nile State. In a separate statement, the SPLM-IO accused the South Sudanese Army of launching attacks against opposition-held bases across South Sudan, notably in oil-rich Unity State, and of preparing for a major assault on rebel positions. They cited SPLA troop movements in the area and military buildup in Jonglei State.

Deciding not to wait for Machar to return to the capital, President Kiir announced next steps towards the formation of a transitional government in mid-Februrary. He announced plans to name a partial cabinet, although he has not yet received input from the SPLM-IO about the 10 ministerial positions they have been promised. The Joint Monitoring and Evaluating Commission (JMEC) asserted that all parties should be present and engaged in the creation of a new government, and that unilateral action would undermine peace efforts.

Per the August peace agreement and Machar’s demands, SPLA forces withdrew from Juba on February 18 in a move towards the demilitarization of the capital. According to the JMEC, the entire demilitarization was expected to take six more weeks. Many believed an extra six weeks was too long to wait to form a new government. The JMEC stated that they were reaching out to both sides to reach an acceptable compromise on security arrangements.

Additional political uncertainty and instability has continued to drive conflict in the country, with the SPLM-IO alleging that the SPLA is continuing an offensive across Greater Mundri in Western Equatoria State in an attempt to dislodge opposition positions in the area. An opposition spokesperson claimed that opposition forces underwent heavy shelling and were forced to withdraw from a number of bases due to SPLA attacks. In Wau State, hundreds fled fighting between SPLA and IO forces. On February 18, a UNMISS base in Malakal sheltering over 200,000 civilians came under heavy fire, resulting in the deaths of 18 people. The UN reported that Dinka and Shilluk youth armed with small arms and machetes began attacking the camp, displacing over 26,000 people.

Political instability and violence continue to destabilize and aggravate the already fragile severe humanitarian situation in the country. The UN has desperately appealed for monetary assistance, reporting that over 40,000 civilians are at catastrophic risk for starvation.

Sudan: Darfur

Jason Qu

New fighting ravaged Darfur in late January as the Sudanese Armed Forces began a broad new offensive in the tumultuous region, most notably Central Darfur’s Jebel Marra. Jebel Marra is a mountainous area and a stronghold for the Darfuri rebel group, the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM-AW), led by Abdel Wahid. Despite a one-month extended ceasefire by Khartoum, the Sudanese army and SLM-AW engaged in intense fighting east of Jebel Marra, displacing tens of thousands and killing dozens. Both sides produced conflicting statements regarding the clashes. This raised new doubts amid a commitment by the Sudanese Government to hold a referendum on the status of Darfur on April 11 to 13, although it has received opposition from some Darfuri leaders, rebels, and political factions.

The “Sudan Call” opposition alliance, a loose coalition of major armed and political rebel groups in the country, called for Darfuris to boycott the referendum on the administrative status of Darfur. Just days after, Darfuri displaced persons and refugee associations did the same. The referendum in Darfur had already been met with intense division in the Sudanese Government, and this announcement seriously threatened a major part of Bashir’s National Dialogue agenda for reconciliation. Using a proposal drawn up by the African Union Peace and Security Council, opposition forces asserted that their ideal solution to the crisis in Darfur would include the dissolution of Sudan President Omar al-Bashir’s Government and a replacement of the 2011 Doha Agreement. In the past, Khartoum has rejected such moves.

Informal talks were held between leaders of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) and the Sudanese Government in Germany, a nation that has signed an agreement with the AU to work with parties to the conflict in Sudan to help find peace. Despite initial optimism that a peace agreement was imminent, the talks collapsed in late January as both sides traded accusations for the lack of progress. Stumbling blocks, notably disputes over humanitarian aid, remained before an agreement could be made to end the 4-year conflict in Blue Nile and South Kordofan. The collapse came as the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) and Sudan Liberation Movement-Minni Minnawi (SLM-MM) began discussions with Khartoum in Ethiopia. These groups, active in Darfur, seek an alternative framework to finding peace in the region besides the 2011 Doha Document.

In early February, after weeks of fighting with Darfuri rebel groups in Jebel Marra, the Sudanese Army claimed key territory. As they regained control of the area, they stated that displaced civilians should return home. Major rebel organizations such as the SLA-AW made statements that fighting was still ongoing. However, neither claim was confirmed. Over 44,000 civilians were uprooted from their homes as a result of the clashes, with the United Nations stating that these civilians faced a “dire” humanitarian situation. There were reports of armed militiamen charging “passage fees” for those fleeing from bombardment in East Jebel Marra. Despite these challenges, a shipment of aid from the UN reached over 20,000 civilians in North Darfur seeking refuge in a UNAMID base.

Central and West Africa: Central African Republic

Ruhi Bhaidani

In late January, hundreds of people marched through the Central African Republic denouncing the fraud of the parliamentary election and calling for a rerun of both the parliamentary and presidential elections. “The aim of this peaceful march is to demand the constitutional court to cancel both polls since the same causes produce the same effects,” said Josephine Ngbaboulou, spokesman for the Alliance of Democratic Forces for Transition. Although demonstrations are officially banned during the election period, protesters gathered at the entrance of the office of the United Nations Peacekeeping Mission in Bangui, demanding the court to act.

The constitutional court in the Central African Republic decided that December’s parliamentary elections must be rerun due to irregularities. This decision came after over 400 complaints, primarily regarding spoiled ballot papers, were lodged by individuals who had participated in the election process. In December, CAR’s election authority admitted that ballot papers for legislative candidates had not arrived in certain parts of the nation, and called for a rerun and recount of votes. A second round of elections was held on February 14, after which CAR was left with a new president but no new parliament. According to Lewis Mudge, a CAR researcher at Human Rights Watch, “These elections were never going to be a silver bullet for Central African Republic. Fundamentally, the ongoing crisis in the country is due to generations of bad governance and corruption.”

The two candidates for presidency, Anicet-Georges Dologuele and Faustin Archange Touadera, are both former prime ministers of the country. Dologuele’s platform includes promises to reformthe country’s troubled finances and attract foreign investment. Touadera is running to end corruption and bring unity to the nation. According to Mohamed Malick Fall, the CAR’s UNICEF representative, children have been dragged into the war, with as many as 10,000 recruited by armed groups during the crisis. He stated that the voices of the children are extremely important as they are the generation responsible for peacekeeping in the future. Preliminary results showed former PM Faustin-Archange Touadera as the expected winner. On February 20, 2016, Touadera won the run-off with 62.71% of votes according to the Election Commission.

In the days leading up to the election rerun, Hillary Margolis of Human Rights Watch commented for NPR that, “People are quite hopeful that it [the election] could bring some form of stability, which is sorely needed in the country. But the fact remains that there do continue to be abuses perpetrated by all parties to the recent conflict. And this government will really have to take action to make sure that systems are put back in place that the rule of law is instated or reinstated and that perpetrators of crimes are held to account.”

In addition to the presidential frenzy, four new accusations of sexual abuse and exploitation against minors by U.N. peacekeepers in the CAR surfaced in February. According to Deputy spokesperson Farhan Haq, the four children lived in the Ngakobo displaced persons camp and were abused as well as exploited in the past two years. The United Nations will start publicly tracking sexual abuse and exploitation cases in the coming weeks.

In Bangui, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams distributed hygiene and cooking kits to 560 families who lost their living spaces and shelters in a fire on February 10 in the Batangafo camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) that hosts about 30,000 people. Five injuries were treated at an MSF hospital. “This situation shows once again the extremely precarious situation in which thousands of Central Africans are living,” said MSF’s head of mission for the CAR, Miroslav Ilic. “Families are living with almost nothing at all and fearing for their basic security every day. The humanitarian crisis in this country is far from over,” he added. In a nation with over 450,000 IDPs and thousands more who have fled the country as refugees, violence and robberies against average civilian have become rampant, adding to the difficulty of citizens’ everyday lives. Reims Pali, an MSF Assistant Field Coordinator, spoke of the refugee camps: “In comparison to the abuses, killings, robberies and lootings that the people have witnessed in their neighborhoods, they feel relatively safe here. But the living conditions in the sites are very difficult. They live in tents built of waste tarpaulins that are full of holes. They sleep on mats on the ground and are exposed to mosquitoes which may carry malaria. Unless the security situation gets better, they will have to stay here in these camps.”

Southeast Asia: Burma

Sophie Back

The newly elected National League of Democracy (NLD) spent the beginning of the year readying itself to take office in February. However, many have doubted whether the new government will be able to bring about the ‘wind of change’ that it promised voters in November. In order to avoid angering the military, the NLD announced that Aung San Suu Kyi will not be assuming the presidency, but intends to lead the country through a ‘ceremonial head of state.’ Furthermore, the NLD will include at least one minister of the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), the outgoing military-backed government, in its cabinet. Under these conditions change is likely to be very gradual in Burma in the coming months.

Despite the ceasefire agreement signed in October, fighting has continued. On December 31, state troops attacked positions held by the Shan State Army–South (SSA-S) in Northern Burma, killing one of their guards and violating the peace deal. Similarly, on December 27, clashes occurred between the Arakan Army and state soldiers. This ongoing instability in Northern Burma has aided the growth of the region’s opium trade, which currently produces 90% of the heroin trafficked each year through the ‘Golden Triangle,’ an area between China, Burma and Thailand. This adds fuel to the flames of regional conflict.

The Myanmar Union Peace Conference in January sought to reopen dialogue between the government, ethnic armed groups, and political parties to agree on a framework for peace. The Conference concluded with the creation of a Joint Ceasefire Monitoring Committee (JCMC) and the Union Peace Dialogue Joint Committee (UPDJC) which will coordinate peaceful negotiations in the future. The delegates set out four proposals to support the peace process: 1) to broaden the national-level dialogue to involve all minority groups within 3 to 5 years, 2) to convene a second peace conference, 3) to increase the number of women involved in the dialogue to 30% of participants and 4) to uphold honour and respect between participants. However, these are early days yet and the concrete aims of the peace process are yet to be agreed upon.

The NLD and USDP remain virtually silent regarding the future of Burma’s persecuted Rohingya communities. Legal discrimination, poverty, police brutality and sporadic violence are among the top threats to the survival of Rohingya communities in Burma which have intensified since the elections. On January 10, a Rohingya fisherman was shot dead on the Naff river by Myanmar Border Guard Police (BGP).The man is believed to be nineteen-year-old Mohammed Raffique from Maungdaw Township; no explanation has yet been given for his death. Following the crackdown on illegal trafficking in Southeast Asia since last May, human trafficking has slowed due to the rising price of using traffickers which has made leaving Burma unaffordable for most Rohingya people. Reports in mid-January indicated that groups of Rohingya refugees have been escaping desperate conditions in camps in Thailand and Indonesia to continue their journeys to safety. Nonetheless, the majority of Southeast Asia’s refugees remain in a state of limbo, as heads of states are reluctant to take action in defense of their rights.

On January 27 Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) arrested 32 Burmese Rohingya migrants and a Bangladeshi human trafficker attempting to cross into Bangladesh via motorboat near Shapuridip. The six crew members and the trafficker have been arrested pending investigation and the passengers are due to be forcibly repatriated to refugee camps in Burma as soon as possible.

At her first press conference since the new parliament was formed on February 1, Aung San Suu Kyi announced to the world press that it is “not yet time to form a government … don’t be anxious. You will know when the time comes.” Aung San Suu Kyi sought to quiet concerns in Burma about the newly elected National League of Democracy’s (NLD) delay in naming their presidential candidate. The NLD leader has promised that a candidate will be announced by early March, meanwhile the party is in the process of a careful decision-making process which she insisted insists “cannot be rushed.” Next month, members of Burma’s two parliamentary houses and the military will nominate three candidates to compete in the presidential election which will decide who is to replace outgoing President Thein Sein.

Shortly after, a parliamentary member for the Arakan National Party (ANP), Khin Saw Wai, spoke out about the NLD’s plans to amend laws which discriminate religious and ethnic minorities in the country. These include the 1982 ruling that automatic citizenship should be granted only to ‘recognized ethnic nationalities’ and groups that settled in the country before 1823, and the four “race and religion protection laws” which were passed by Parliament last year. The latter have provided a legal basis for discrimination against the Rohingya in recent months. Khin Saw Wai argued these laws offer protection from the perceived threat of “race annihilation” in the Northern Arakan State townships, where Arakanese communities make up just 3 percent of the population. The ANP are threatening to mobilise politically against the NLD’s reforms. Many view this as a reminder to the new government that it will have to negotiate with groups like the ANP, which are driving racial hatred in Burma, to achieve a democratic transition.

Additionally, the European Community Humanitarian Office (ECHO) has raised its concerns about child malnutrition in Burma which has been exacerbated by last year’s floods and has placed added strain on Burma’s persecuted Rohingya communities living in temporary accommodation. Reporting on the conditions of the refugee camps in Rakhine state ECHO’s regional coordinator Roselyn Mullo said refugees are surviving on one meal a day and a diet of predominantly rice and water. 19,200 children under five are currently moderately malnourished in the flood-zone and 1,500 are suffering severe malnutrition. Mullo has predicted that these levels are likely to rise in 2016 and has urged the new government to take immediate action to address Burma’s most vulnerable.

Amnesty International has called for the Burmese government to repeal the ‘Former Presidents Security Law’ passed on January 27, which protects retired statesmen from being indicted for human rights violations committed under their watch. According to Champa Patel, Amnesty International Interim Director South East Asia and Pacific Office has rebuked this law as an attempt by the outgoing government “to protect its ranks from any form of prosecution.” Critics warn that this legislation could seriously undermine Burma’s democratic transition and rob the Burmese people of their right to justice and reparations for the last 25 years of oppression and military rule.

Mid-February, Aung San Suu Kyi came under increasing pressure to increase her level of personal security after a receiving a death threat on Facebook from a man known as Ye Lwin Myint. Ultra-conservative Ye Lwin threatened to shoot anyone who tries amend the article in Burma’s constitution which bars Suu Kyi from being elected president. Further threats were made by Buddhist Fundamentalists in Rakhine State whodemanded that Aung San Suu Kyi ignore calls from the international community to amend the exclusive 1982 citizenship law and grant citizenship rights to the 1 million Rohingya people living in Burma.

Pe Than, parliament member for Arakan National Party told Ucanews.com in late January that “We are ready to fight back on it as we have vehemently called for not amending the law because we need to scrutinize illegal migrants and… consider our race, sovereignty and security.” The threat of ethnic-based and political violence continues to loom large in Burma and many remain resistant to democratic reform.

This week, a report published by the Calcutta Research Group revealed that the number of Rohingya families settled in India has reached 10,565. The report titled ‘Rohingyas: The Emergence of a Stateless Community’ interviewed thousands of Rohingya refugees and studied the precarious position of these families (representing some 40,000-60,000 people) living in India’s refugee camps, particularly those living in Jammu, Hyderabad, Delhi and Kashmir. A key concern highlighted by the report was the widespread incarceration of families seeking refuge in West Bengal where UNHRC refugee cards are not recognized as valid. Reporters claim this harsh treatment is leading to the “disintegration of the refugee family” and has had a profound psychological effect on detainees. This report highlights a new facet of the Rohingya diaspora which is no longer simply a Southeast Asian issue but is now affecting much of Southern Asia.

In Bangladesh, the government has begun it first official census of Rohingya refugees. The study is being conducted in partnership with the International Organization for Migration and will take place over several weeks. It seeks to assess the economic and social conditions faced by stateless Rohingya migrants in through interviews and home visits. Current estimates claim that there are around 500,000 Rohingya refugees living in Bangladesh, however, without a clear understanding about the scale of the issue authorities have been unable to act to improve the situation. Many hope this study will help bring about the decisive action needed to improve the quality of life for Refugees in Bangladesh.

In Kuala Lumpur on February 11, clashes broke out between Rohingya workers and local gangsters, leaving one man dead, a Rohingya worker, and two injured. The violence, which took place in the Selayang wholesale market, was part of a continuing turf-war between the two groups, however, this was the first time that local hostility towards the Rohingya community has led to a killing. It is feared that the incident may lead to further flare ups in the coming weeks.

Middle East and North Africa: Syria

Maddie King

Representatives from both the Syrian government and the opposition attended at the first round of Syria talks in January in Geneva, part of a process outlined in a UN resolution in January providing an 18-month timetable to end the war in Syria. These UN backed negotiations were designed to bring together the Assad Regime and the opposition in order to devise a plan to begin the process of political transition including elections and the drafting of a new constitution. John Kerry confirmed that the two groups would not meet directly, but that negotiations would take place through proximity talks. Russia continued to push for the inclusion of Kurdish groups, who were excluded from earlier talks in Riyadh.

On February 3—just two days after their official start—the third round of Geneva peace talks were suspended and postponed.These negotiations were initially set to begin on January 25, but were pushed back repeatedly as the opposition council (the High Negotiations Committee) formed in Riyadh in December refused to engage in negotiations until Assad’s regime agreed to certain humanitarian measures. These measures included the halting of bombardment of civilian areas, the opening of besieged areas to humanitarian aid, and the release of detainees as a gesture of goodwill.

The collapse of the Geneva peace talks occurred in the context of a dramatically escalated offensive on Aleppo by regime forces, supported by heavy Russian airstrikes. The offensive aimed to cut supply lines to rebel held parts of the city of Aleppo and to end the opposition’s siege on two government held Shiite villages, Nubol and Zahraa. Pro-government forces successfully broke rebel sieges on Nubol and Zahraa and approached Aleppo, with reports indicating that up to 70,000 civilians evacuated the city and its surrounding area in anticipation of a siege of the city. Despite these developments on the ground, Stefan de Mistura, the UN special envoy to Syria, insisted that negotiations would resume. Additionally, the UN held an important donor conference in which world leaders pledged provide nearly $11 billion in aid for Syria in 2016.

Although the first round of the Geneva peace talks were suspended, the the ISSG (International Syria Support Group) announced a cessation of hostilities in mid-February. The agreement came out of a bilateral American-Russian pledge to expand diplomatic and military cooperation and increase the rate of aid delivery to affected regions in Syria, a move congruent with the demands of the rebel groups. The ceasefire did not include international efforts to combat terrorism, and many expressed doubts that Russia’s airstrike campaign may continue to target moderate Syrian opposition forces, despite the aforementioned ceasefire. These concerns were especially potent because the Assad regime continued to advance on Aleppo.

Just days after the ISSG agreed to end hostilities in Syria, Russian prime minister Dmitry Medvedev stated in an interview with Time that Russia would continue its bombing campaign of moderate rebel forces in and around Aleppo. The Russian airstrike campaign, ostensibly intended to target ISIS and al-Nusra targets, has in practice targeted many moderate rebel forces. Many international forces hoped that the recently agreed upon cessation of hostilities would lead to an end of Russian air raids on civilian and rebel forces, but Medvedev’s statements that “they are all bandits and terrorists” left observers with little hope about the end of airstrikes.

Assad also expressed concerns about the feasibility of the planned “cessation of hostilities,” citing issues regarding the proposed time frame and questioning what a ceasefire would mean for terrorists. Despite the potential military complications, the agreement was successful in terms of allowing aid to reach many besieged Syrian towns.

Meanwhile, the crisis in Syria continued to escalate throughout the peace process. Ilya al-Adl, a local leader of the al-Nusra Front, Syria’s al-Qaeda affiliate, was assassinated on January 20 in northwestern Idlib province. More than 20 Islamist leaders and commanders were assassinated in Syria between December and January. Analysts have attributed these assassinations to either the Islamic State or the Syrian government.

The Islamic State made territorial gains in late January, capturing territory including weapons depots and the Saiqa Camp army base from the Syrian government in the northern areas of Deir Ezzor province immediately after a series of defeats. On January 19, ISIS released 270 of the 400 or so civilians abducted in the area, but abducted an additional 50+ men and massacred another 135.

The United Nations continued to mobilize over the severe malnutrition in besieged areas throughout Syria. In early January, the situation in Madaya reached crisis levels when the city of 42,000 suffered a 174 day siege by regime forces. More than 30 died of starvation in early January. On January 7, after international outcry, the Syrian government allowed a first round of aid to reach the area. However, many remain at risk and will continue to be at risk as the conflict continues. The United Nations has declared that world powers will continue to push for the end of sieges across Syria to ensure the health and safety of the 400,000 people under siege nationwide.

As pro-government forces continued to move forward in Aleppo in early February, tens of thousands of civilians fled to the Turkish border. The Turkish government established another refugee camp by the Oncupinar border gate and began providing aid and assistance to incoming refugees. The Syrian government also continues to tighten sieges in other Northern cities and villages. The United Nations estimates that around 450,000 Syrians are living under siege, but a report issued by Siege Watch and the Syria Institute challenged this figure, estimating that some 1.09 million people are living in besieged areas throughout Syria.

Turkey also launched a series of massive artillery bombardments against Kurdish targets in northwestern Syria, hitting an air base recently reclaimed from the Islamic State. Ankara claimed these attacks were a “retaliation” against Kurdish attempts to form an independent state in Northern Syria. The attacks received condemnation from the ISSG, which called for an increased focus on fighting ISIS and seeking political solutions in the region.

In late February, Turkey continued to fire artillery units on positions held by U.S.-backed Syrian Kurdish militants in Northern Syria, claiming to be in response to Kurdish fire. Ankara has become increasingly worried about YPG territorial gains along the border due to YPG’s political affiliation with the outlawed Kurdish Workers Party. Turkey has also blamed Wednesday’s car bomb attack on a Syrian Kurdish militia fighter, despite denials from Kurdish groups.

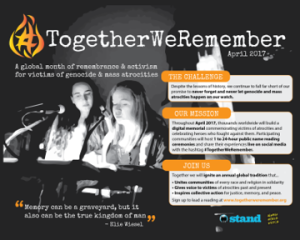

STAND’s network of individuals, successfully published several op-eds and blog posts, and held multiple call-in days on a range of issues including the Elie Wiesel Genocide and Atrocities Prevention Act, U.S. involvement in the conflict in Yemen, and attacks on U.S. refugee resettlement, including the Muslim Ban. In addition, our Education and Communications Task Forces covered a range of conflict areas in their pieces including less highlighted areas of injustice such as Guatemala, Punjab, and Indonesia.

Savannah Wooten

Savannah Wooten