STAND’s conflict updates come to you from STAND Education Task Force, a group of student experts from across the U.S. dedicated to providing through analysis of STAND’s conflict areas to our grassroots base. This conflict update focuses on international action regarding the Rohingya crisis in Burma and Bangladesh, struggles surrounding Yemen’s port city of Hodeidah and the man-made famine that has ensued, and several tentative ceasefires and peace deals, including in Darfur, South Sudan, and Djibouti.

Southeast Asia

Burma

Violence against the Rohingya in Burma continues to contribute to a mass exodus, with the number of refugees in Bangladesh topping 725,000. Even in exile, Rohingya face inhumane conditions as the Bengali government is not able to adequately meet the material needs of the refugees, and insists Burma uphold their agreement to readmit Rohingya refugees. Despite Burma’s expressed intention to comply, the vast majority of Rohingya refugees do not want to return unless they are guaranteed citizenship rights, recognition as a minority group, justice for crimes committed against them, return of their homes and property, and assurance of their security. The Burmese government granted permission for the UN to assess 23 villages “where Rohingyas were allegedly murdered and subjected to attacks, imprisonment and sexual violence at the hands of the Myanmar military.” The investigation will aim to determine the potential dangers associated with return of Rohingya refugees and could be the first step towards repatriation back into Burma.

Last month, two journalists were sentenced to seven years in prison for documenting a massacre of Rohingya Muslims. Their arrest prompted major international uproar, as world leaders condemned Burma’s disregard for freedom of religion and press. Aung San Suu Kyi, a nobel laureate and the de facto political leader in Burma, denied allegations that the arrests violated freedom of expression. In the same speech, Suu Kyi admitted that the plight of the Rohingya “could have been handled better,” but failed to admit to the scope of atrocities committed. Canada has been the latest to publicly condemn Suu Kyi, voting to publicly declare the situation a genocide last month, and stripping Suu Kyi of her honorary Canadian citizenship this week.

The U.S. State Department released a report last week that surveyed over 1,000 Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh and documented atrocities in Northern Rakhine State over the past two years. The 20-page report contributes to a growing body of evidence surrounding crimes committed by Burmese security forces, but provides no policy recommendations for the U.S. government.

Sudan and South Sudan

Sudan

A British delegation visiting Sudan in late September condemned the hastened pullout of the UN-African Union Hybrid Operation (UNAMID) that was halved just 3 months ago. The parliamentarians in the delegation posited that the relative stability in the Darfur region may be disturbed by the withdrawal and that displaced persons still living in camps would likely be negatively impacted. Delegation leader and MP David Drew warned that “Withdrawing too quickly without a clear plan puts the progress made in Darfur at risk.”

President Omar al-Bashir reduced the number of government ministries from 31 to 21 on September 10 due to economic hardship and a lack of funding. Economists have denounced the move, saying it will have little impact on Sudanese markets. Last month, Sudan’s ruling National Congress Party (NCP) selected Bashir as its candidate for the 2020 election. Bashir, who has ruled the country since 1993, had previously said he would step down when his current term ends. The International Criminal Court first issued a warrant for Bashir’s arrest in 2009 for crimes against humanity, murder, extermination, forcible transfer, torture, rape, war crimes, and three different counts of genocide.

In the wake of governmental uncertainty, violence and natural disaster continue to threaten the lives of civilians. More than 50 people died in a remote part of Jebel Mara when heavy rainfall caused a hill to collapse on a village in mid-September, and, in a rare demonstration of concern, on September 19 the Sudan Liberation Movement-led by Abdel Wahid al-Nur (SLM-AW) declared a three-month ceasefire to allow humanitarian aid to access civilians in affected areas.

South Sudan

On September 12, President Salva Kiir and rebel leader Riek Machar signed a peace deal in the latest bid to end the civil war. The agreement, which was mediated by Sudan and signed in Ethiopia, formally reinstated Machar as vice president and made plans for a transitional government to be established in the coming eight months.

The peace agreement stems from a preliminary deal drafted in June and negotiations throughout the summer. Machar had previously refused to sign the latest version of the deal in late August due to disagreements over power-sharing mechanisms and the new constitution. In early September, the UN Refugee Agency brought sixteen South Sudanese refugees to the talks to share their hopes and expectations for the peace process.

Large segments of the international community look upon the deal with cautious optimism, as various peace agreements and approximately ten ceasefires have failed in the last five years. In June, for example, a ceasefire was violated just hours after it began. Kiir acknowledged international skepticism in a statement, stressing that doubt would fuel his resolve to consolidate peace. Two days after this statement was issued, however, fighting broke out in Central Equatoria state. The Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring Mechanism announced an investigation in the ceasefire violation on September 14. The inquiry has not yet identified the actors who initiated the violence or discussed potential implications for the peace deal.

The UN Human Rights Commission on South Sudan called for the government to establish a hybrid court to prosecute war criminals on September 17. The Commission heard testimonies of wanton killings and sexual violence that same day and examined food scarcity in the country. On September 19, Amnesty International published a new report based on testimonies of approximately 100 civilians who fled a government-led offensive between late April and early July. ‘Anything that was breathing was killed’: War crimes in Leer and Mayendit outlined shocking cases of unlawful killing of civilians, abduction, sexual violence, detention, looting, destruction, and forced displacement.

Middle East and North Africa

Yemen

With Yemen’s largest port, Hodeidah, continuing as a battleground in the country’s civil war, humanitarian efforts in the country are rapidly deteriorating. Since July, the Saudi Arabia and UAE-led coalition has intensified the conflict between rebel groups and the Yemeni government in the Hodeidah area, resulting in more than 100,000 civilians fleeing the city. Those who remain live in constant fear of violence. Humanitarian efforts have been reduced as the port is no longer safe for use, placing all Yemenis at risk.

The Hodeidah port is critical to the stability of the Yemeni population, serving as the primary location for the international community to distribute aid during the conflict. The port routinely received food, water, medicine, and other resources before the coalition turned began its campaign in the area.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE first began the initiative to defeat and weaken the Houthi rebels’ control of Hodeidah in 2015, with a coalition of 9 African and Middle Eastern countries, aiming to defeat the Houthis’ challenge to the legitimacy of the Hadi Yemeni government. While the coalition and rebel groups continue to fight, a fundamental issue remains: the safety of the Yemeni people. Since the war started in 2014, 50,000 people have died from the ongoing, and man-made, famine. Nearly 10 million are at risk of famine, half of whom are children. The situation in Hodeidah continues to exacerbate the effects of the ongoing famine, putting the lives of millions more at risk. If a solution is not found, and soon, the entire population will become more susceptible to famine as no food nor aid will enter the country.

In addition to food resources, Yemen must be able to accept medicine and vaccines through their ports in order to fight the growing cholera outbreak. Crumbling water and sanitation sources have cut off clean water for an estimated 15 million people, with The World Health Organization estimating that more than 1 million cholera cases are present in the country.

Horn of Africa

Eritrea and Djibouti

Last weekend, Eritrea and Djibouti underwent a “full normalization” of relations after almost a decade of border disputes between the two nations and multiple failed mediation efforts by neighboring countries and the UN Security Council. Past alterations at the border have cost dozens of Djiboutian lives and have brought diplomatic relations between the two countries to a halt. Many hope that the returning of border land will bring back trade and peace to the region.

Despite the thawing of relations between the two nations, many critics and foreign affairs experts remain skeptical. State Department Assistant Secretary for Africa Tibor Nagy admires the progress that the leaders have made in fomenting regional peace but retains that it is too soon to gauge whether United Nations sanctions imposed in 2009 should be lifted. Furthermore, Eritrea’s authoritarian inclinations continue to strain regional cooperation, with events such as an apparent weapons purchase from North Korea calling into question the country’s commitment to its neighbors.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia has continued to take slow steps toward improving civil society by freeing journalists and lifting internet and media restrictions. Rebel groups and famous opposition leaders have returned to Ethiopia amidst the newfound peace.

Somalia

The United States government is still slowly fighting Al-Shabaab forces in Somalia. Earlier last month, two Al-Shabaab militants were killed by the U.S. military on Somali soil. To date, the government of Somalia has paid over $400,000 to lobby the U.S. to end the ban on travel between Somalia and the U.S.

Two young girls have bled to death after their genitals were forcibly mutilated. Somalia’s Deputy Prime Minister has spoken out against the practice of female genital mutilation, but since an initial push in 2012, the practice has practically remained untouched by policymakers. According to Time, “in Somalia, 98% of women and girls between the ages of 15 and 49 have been cut, the highest rate anywhere in the world.”

–

Ellen Bresnick is a sophomore at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, and is serving as STAND’s Great Lakes of Africa Coordinator for the 2018-2019 academic year.

Angela Wei Jiang is a sophomore at Columbia University and is serving as STAND’s Horn of Africa Coordinator for the 2018-2019 academic year.

Abhav Soni is a junior at Middleton High School in Madison, Wisconsin, and is serving as STAND’s Middle East and North Africa Coordinator for the 2018-2019 academic year.

Maya Ungar is a junior at the University of Arkansas and is serving as STAND’s Southeast Asia Coordinator for the 2018-2019 academic year.

Isabel Wolfer is a senior at The George Washington University in Washington, DC, and is serving as STAND’s Communications Coordinator and Sudan and South Sudan Coordinator for the 2018-2019 academic year.

ration was carried out through

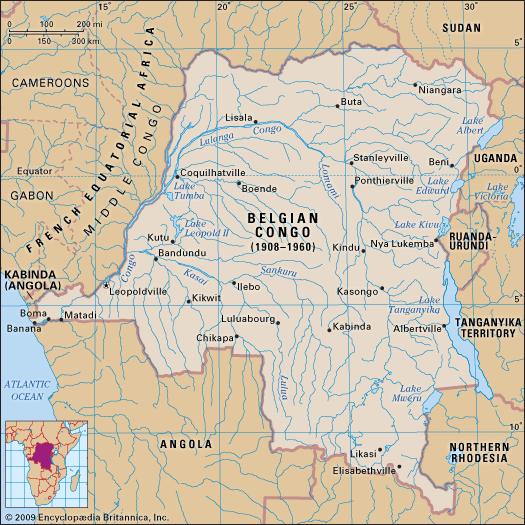

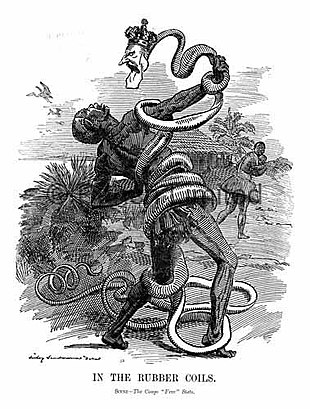

ration was carried out through  s position of relative weak economic and military power amongst its European counterparts, King Leopold sought to consolidate the Congo Free State as a consistent source of revenue for the Crown. He achieved this by partitioning the territory into commercial zones and encouraging European companies to set up industries to extract natural resources while harvesting the most abundant of resources: labor. By forcibly compelling the indigenous population to work in the harvest and production of primary commodities, notably rubber, Leopold set up a system of slave labor designed to transfer wealth from Congo to Europe with no regard for the livelihood of the Congolese.

s position of relative weak economic and military power amongst its European counterparts, King Leopold sought to consolidate the Congo Free State as a consistent source of revenue for the Crown. He achieved this by partitioning the territory into commercial zones and encouraging European companies to set up industries to extract natural resources while harvesting the most abundant of resources: labor. By forcibly compelling the indigenous population to work in the harvest and production of primary commodities, notably rubber, Leopold set up a system of slave labor designed to transfer wealth from Congo to Europe with no regard for the livelihood of the Congolese.