Alongside numerous other peace-focused organizations, STAND has been at the forefront of advocacy efforts for the Global Fragility Act (GFA) since it was first introduced in both the House and Senate in 2018. The GFA outlines a whole-of-government approach to shift U.S. engagement in fragile states toward preventing or stabilizing conflict. The GFA stipulates that USAID, the State Department, the Department of Defense, and other agencies must work together to craft a 10-year plan for 5 countries or regions selected on internationally recognized indicators of fragility in order to streamline a coherent U.S. foreign policy regardless of personnel or administration shifts. It acknowledges that for the attainment of sustainable peace, strengthening governance and civil society to combat fragility must be done through a long-term emphasis on bottom-up, locally-led peacebuilding measures.

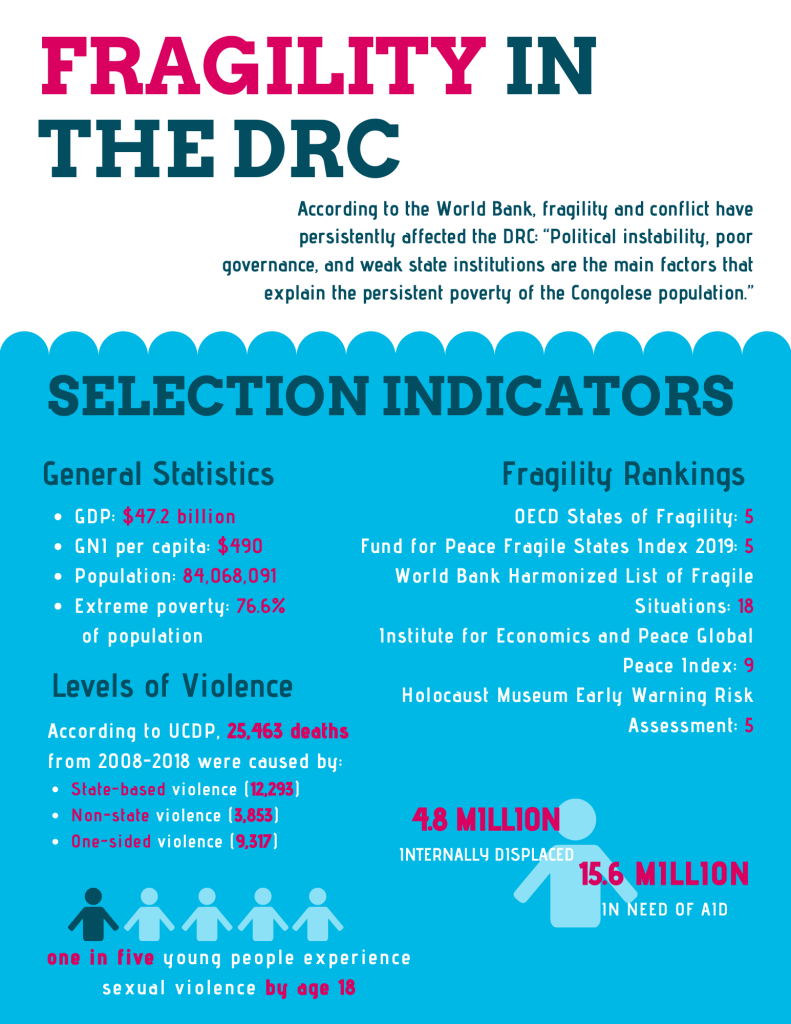

While we celebrate the inclusion of the Global Fragility Act in the FY2020 US appropriations package, which was signed into law in December 2019, we must now turn efforts toward ensuring implementation. To encourage various agencies to work together in order to fully implement GFA, this blog serves as an example of how the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) could be among the 5 countries or regions selected, based on criteria laid out in the Act, in the category of countries where the priority will be stabilizing ongoing conflicts.

Historical Background

Protracted conflict in the DRC has created one of the largest humanitarian crises in the world. The three decade long dictatorial rule of Mobutu Sese Seko, supported by the United States among other Western states, resulted in a deterioration of state capacity, consolidation of power, and widespread exploitation of resources and the population. An estimated 2 million Hutu refugees fled Rwanda to camps in eastern DRC fearing reprisals from the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) government after the 1994 genocide. The genocidaires began remobilizing within refugee camps based in the DRC and by 1995, the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) slowly closed the camps. Meanwhile, the Rwandan government initiated cross-border military operations into the DRC to curb mobilization of former perpetrators of genocide. Along with Uganda, they provided support for the 1996 uprising against President Joseph Mobutu, who had been in power since 1965. In the political vacuum created by Mobutu’s forced removal, Laurent-Desire Kabila captured the presidency, ending Congo’s “first” war.

As both regional and internal tensions continued mounting, Kabila further deteriorated state capacity of the DRC while exploiting both the country’s population and resources. When Rwanda and Ugandan forces invaded in August 1998, other countries came to the DRC’s defense. Meanwhile, local militias and community self-defense groups proliferated across the country – some independent, some tied to Congolese elites, and still others funded by foreign countries. By 1999, the six involved countries and some rebel groups signed a ceasefire, though the many that did not continued fighting. After the assassination of Laurent Kabila, his son, Joseph, took the presidency. See STAND’s one-pager for more conflict background preceding the 2016 elections.

Recent Events

Though the decade-long war officially ended in a 2002 peace agreement, violence has persisted and Kabila consistently delayed his relinquishment of power. As state governance weakened, lower-level elites gained power and localized armed groups continued to proliferate, especially in the Ituri and both Kivu Provinces. While consistently at the top of list of fragile situations, violence has recently spiked across the country. Intercommunal violence has increased in the western regions of the DRC, particularly in the Yumbi province. However, the most concentrated violence consistently occurs in the eastern provinces bordering Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi. Here, at least 130 armed groups operate in North and South Kivu, jointly referred to as the “Kivus,” alone. In 2018, the Kivu Security Tracker found that 8.38 per 100,000 civilians were killed; the 2018 death rate in Borno, the Nigerian state in which Boko Haram and Al Qaeda are most active, was 6.87 per 100,000. The protracted conflict often falls along ethnic divisions, though the complex landscape is also marked by other regional, domestic, and international motives. At the heart of violence in the Kivus is the Beni territory, where fighting between Congolese military personnel and the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), among other armed groups, in addition to recurrent targeted mass killing have killed over 1,000 civilians while displacing nearly 200,000 others.

Pandemics have both exacerbated and been exacerbated by conflict, with numerous outbreaks including measles, cholera, monkeypox, and Ebola Virus Disease (EVD), the latter having been recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a global health crisis. Public mistrust rooted in negative historical experience with foreign interveners has hindered the ability of foreign healthcare workers to adequately trace and treat the spread of the diseases. This is especially visible with the EVD epidemic, which began in eastern DRC.. Since the beginning of the epidemic, numerous attacks on treatment centers by various armed groups have hindered the ability of healthcare workers to adequately reach populations in more rural areas. Further, most external donor funding has largely focused on the EVD outbreak, while other epidemics continue spreading amidst mass killing. Recently, the WHO reported that a Beni EVD treatment center discharged Masiko, the DRC’s last confirmed EVD case; while the end of the outbreak is close, the WHO still urges to remain in “response mode” to avoid reignition of an outbreak. On the heels of the containment of EVD, the global COVID19 pandemic has begun to spread, recently killing the aide of current president Tshisekedi.

Despite challenges such as these, the DRC purportedly experienced its “first-ever, peaceful democratic transfer of power” on January 24, 2019, when Felix Tshisekedi became current president. However, reports from independent Congolese civil society groups found evidence of corruption and fraudulence immediately following the elections. Despite abundant proof that Martin Fayulu, the opposition candidate, had actually secured the majority vote, the U.S., among many other countries, supported Tshisekedi. Experts speculate that he and former president Kabila forged an alliance, enabling Kabila to retain a significant amount of influence in Congolese politics after surpassing his legal presidential term limits by two years.. Throughout the election process, the Kabila administration took clear steps to intimidate and hinder voters. On election day, the Kabila administration blocked the votes of 1.2 million Congolese citizens in the North Kivu province, allegedly an opposition stronghold, claiming that violence and the EVD outbreak made polling stations too vulnerable. Still, civil society activists work for peace and electoral integrity.

Current U.S. Priorities in DRC

The U.S. contributes about half of all humanitarian assistance in the DRC as their largest bilateral donor; the U.S. is also the single largest financial contributor to the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO). The Department of State states that the U.S. is interested in “supporting the country to uphold democratic processes and effective governance, promoting stability and peace within the country and with its neighbors, improving the rule of law to strengthen state authority across its territory, and developing institutions that are accountable and responsive to the basic needs of its citizens.” After the December 2018 elections, U.S. engagement led by the Bureau of African Affairs especially supported “a peaceful democratic transfer of power” while “addressing the root causes of conflict and instability in the region.”

Despite substantial U.S. and international contributions to peacebuilding and stabilization efforts, sustained peace has proved elusive. In the 2015-2021 USAID Country Development Coordination Strategy (CDCS), USAID assumes that U.S. support for building peace in the DRC takes a whole of government approach. It states that “[i]f the USG as a whole, including the Department of State and the Department of Defense, does not work closely to address the crisis in eastern DRC, there will be no chance of lasting peace.” This shows that the DRC would be a relevant candidate for the GFA, which requires interagency coordination in all country strategies.

Country Plan Recommendations

Increase funding and spending for bottom-up peacebuilding initiatives led by local civil society organizations that address root causes of conflict. This measure would support local conflict resolution that can in turn promote enabling environments for success of national peace processes. Money allocated and requested should be increased, and actual spending should follow. Funding to local peacebuilders should be flexible in order to learn and adapt rapidly to local needs, and ensure autonomy of initiatives for maximum impact. Supporting community-based conflict resolution mechanisms already form an important aspect of USAID’s current CDCS for the DRC.. Accordingly, other agencies should act toward this goal by implementing local voices in security sector reform plans and diplomatic engagements.

Ensure adequate allocation and spending of funds toward peace and security. During FY2019, the bulk of foreign assistance requests from the President and allocation by Congress were to the Health and Humanitarian Assistance sectors. Still, both set aside more substantial funds than what was actually spent on Peace and Security and Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance, both of which can help address the roots of conflict. While it can alleviate the short-term suffering of the Congolese people, the current way the foreign assistance budget to the DRC is spent will not contribute to the long-term change needed.

Encourage the United Nations and African Union to support regional diplomacy between DRC and other countries of the African Great Lakes region. With an increase in armed group activity, many of which have ties to neighboring countries, supporting regional diplomacy can help to cut or diminish support for violent armed groups operating in eastern DRC.. International intervention has not been effective nor sustainable in demobilizing these groups nor in stabilizing the region.

Collaborate closer with those who know the situation best. In order to create the most inclusive and effective strategies, close collaboration with local peacebuilders can generate better processes and strengthen accountability. This can include establishing indicators for monitoring and learning based on local-level needs, ensure leadership in missions from foreign service nationals to establish strong local relationships and better continuation through American staff rotations, supporting civil society to get involved in national peace processes, understand what value-added international supporters can have from local peacebuilders, and necessitate participatory research methods in conflict analysis and program evaluations.

Ensure accessibility of grant allocation processes to a wider range of local initiatives. This would include increasing support to youth peacebuilders who, especially in the DRC, have been making innovative and tangible change for the status of peacebuilding in the country. Many grants awarded are larger than some small, local initiatives need, and should be adjusted to include microlending for smaller-scale initiatives.

–

The structure of this blog was inspired by briefers by the Alliance for Peacebuilding on the Central African Republic and Bangladesh as Stabilization and Prevention candidates for the GFA, respectively.

–

Megan Smith is a senior at the University of Southern California, a member of STAND’s Managing Committee, and an intern at the USC Shoah Foundation. Previously, she served on the Policy Task Force of STAND France during her junior year and as California State Advocacy Lead during her sophomore year. Outside of STAND, she has interned at Dexis Consulting Group (Washington, DC), DigDeep Water (Los Angeles), and HAMAP-Humanitaire (Paris).