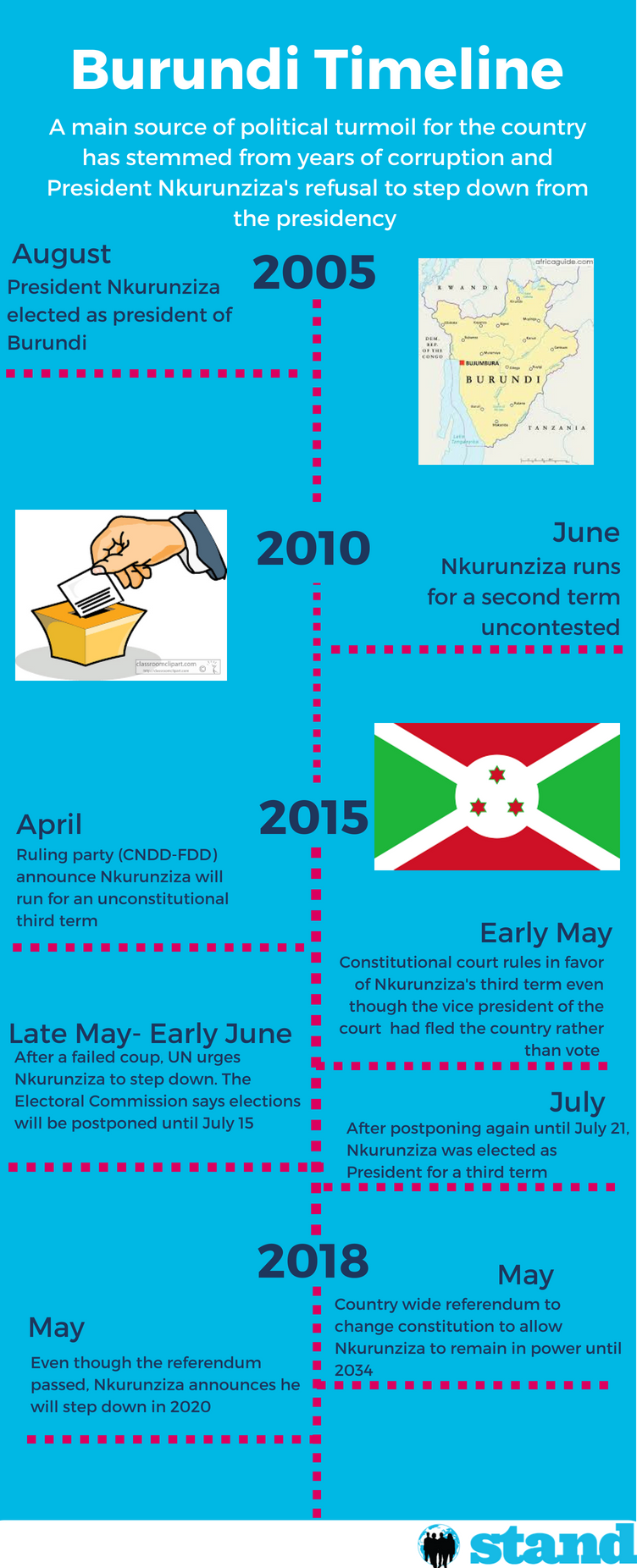

Last month, three years after conflict broke out in Burundi due to President Pierre Nkurunziza’s decision to run for an unconstitutional third term, the country voted on a referendum for constitutional reform. The referendum would allow Nkurunziza to remain in office until 2034. The May vote was preceded by months of intimidation and violence used by the ruling party to coerce citizens into voting in favor of accepting the referendum.

After a civil war between the majority Hutu ethnic group and minority Tutsi that lasted from 1993 until 2005, the Arusha Peace Accord was signed, which established a power sharing government. In 2005, Nkurunziza, a member of the CNDD-FDD party, was elected as president by Parliament. In 2010, he was re-elected by popular vote. In 2015, he argued that since he was not elected by popular vote, but by Parliament, for his first term, that it did not count as a formal first term, and he would run for another term. Conflict erupted around the country. Despite this, Nkurunziza ran and won elections held in July 2015, which also was surrounded by intimidation from Nkurunziza’s party and the police. These elections were boycotted by the opposition. Since 2015, opponents, suspected opponents, human rights activists, and journalists have all faced violence at the hands of the government. Around 1,700 have been killed and many others have been disappeared, raped, tortured, beaten, and randomly detained, and about 400,000 people have fled the country. On May 11, 26 people were brutally killed in Ruhagarika village in Cibitoke province. It is unclear who perpetrated this attack and whether it was related to the referendum, but it serves as a stark example of the instability in Burundi surrounding the vote.

The referendum took place on May 17, with months of escalating fear and violence in the lead up. The government issued threats to those who opposed the referendum, stating that they would arrest anyone who campaigned against it. The text of the referendum was not published until May 8, 9 days before the vote, and it was hidden deep within the National Independent Electoral Commission website. No link was publicized and it had to be “thoroughly searched to be found.” A recent briefing by the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi to the UN Human Rights Council detailed some of the violence and intimidation that occurred leading up to the referendum vote. Nkurunziza and his party made threats with “barely concealed incitements to hostility or violence.” Many who advocated against the referendum, asked to meet about the draft amendment, or refused to join the CNDD-FDD, were arrested and often tortured. Some opposition members were killed or abducted. Several remain missing and unidentified bodies continue to be found throughout Burundi.

The referendum took place on May 17, with months of escalating fear and violence in the lead up. The government issued threats to those who opposed the referendum, stating that they would arrest anyone who campaigned against it. The text of the referendum was not published until May 8, 9 days before the vote, and it was hidden deep within the National Independent Electoral Commission website. No link was publicized and it had to be “thoroughly searched to be found.” A recent briefing by the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi to the UN Human Rights Council detailed some of the violence and intimidation that occurred leading up to the referendum vote. Nkurunziza and his party made threats with “barely concealed incitements to hostility or violence.” Many who advocated against the referendum, asked to meet about the draft amendment, or refused to join the CNDD-FDD, were arrested and often tortured. Some opposition members were killed or abducted. Several remain missing and unidentified bodies continue to be found throughout Burundi.

Much of the violence since 2015 has been perpetrated by the Imbonerakure, the youth wing of the CNDD-FDD. In the lead up to the referendum, they set up roadblocks around the country to check receipts for contributions. These contributions are for the 2020 election and are supposed to be 10% or more of one’s monthly salary. Citizens have been pressured to pay these contributions on top of taxes and other required fees despite the fact that 3.6 million Burundians, or about 30% of the population, are in need of humanitarian assistance. Prior to the vote, people were often required to show a receipt of voter registration to enter markets. The BBC and Voice of America broadcasts were banned in the country after they were accused of discrediting the president. In res

ponse to the Commission’s accusations, the Burundi Ambassador to the UN, Renovat Tabu, claimed the Commission to be politically biased and that “his country reserves the right to bring to justice those who defame the government.”

Along with changing the term limit from five to seven years, the referendum would also change the number of vice presidents from two to one. As required in the Arusha Accords, there are currently two vice presidents: one Tutsi and one Hutu. Moving forward, however, the now singular vice president will come from a different political party and ethnic group than the president, but a prime minister, who holds more power than the vice president, will be selected by the president – meaning they will most likely come from the same political party and ethnic group. The referendum also changes the requirement that laws must pass by a two-thirds majority in parliament and now requires only a simple majority. Because the current quota requires 60 percent of parliament to be Hutu and 40 percent to be Tutsi, this will give Hutu a permanent majority in all votes and will prevent Tutsi from having much power in parliament. The referendum also requires ethnic quotas to be reviewed in the next five years. All of these changes could lead to more ethnic conflict.

The quotas established by the Arusha Accords allowed for a government comprised of both Hutu and Tutsi leaders to prevent one ethnicity from holding all power – a main cause of much of the violence and conflict in Burundi throughout the 20th century. Before the referendum vote occurred, the opposition stated that they would not accept the results, pointing to claims that the process was not fair or democratic because of violence used by government forces against anyone opposing the referendum. The referendum passed with 73 percent of the vote. However, this number most likely does not reflect real opinions, as demonstrated by reports of intimidation, violence, and claims of rigging.

Soon after the results came out, Nkurunziza announced that he would not seek reelection in 2020. Many hope this will means violence will stop, but much of the opposition is skeptical that Nkurunziza will actually step down. They say he has lied to them consistently, including lying about abuses his party has committed, claiming that none have occurred.

Most news articles about Burundi in the last two months have focused on violence and intimidation before the vote and on Nkurunziza’s announcement to not run in 2020, and have not discussed the conditions surrounding the vote and conditions in the country in the month and a half since. Even the UN Commision of Inquiry on Burundi briefing, while published at the end of June, focuses only on human rights abuses in Burundi before the vote. This makes it challenging to understand how the referendum results and Nkurunziza’s announcement have and will affect Burundi in the future. However, with the CNDD-FDD’s recent behavior and with the referendum changes that challenge ethnic requirements established by the Arusha Peace Accord, the future of Burundi does not look optimistic. It is clear that even if Nkurunziza does step down, Burundi will remain unstable and divided, and elections in 2020 are likely to occur alongside continued violence and conflict.

–

Hannah King is STAND’s Campaigns Coordinator for the 2018-2019 school year. She is a rising senior at Clark University, where she studies Sociology, Political Science, and Holocaust and Genocide Studies. This summer, she is interning at Aegis Trust in Rwanda after spending the spring semester there studying post-genocide reconstruction and peacebuilding.

Hannah King is STAND’s Campaigns Coordinator for the 2018-2019 school year. She is a rising senior at Clark University, where she studies Sociology, Political Science, and Holocaust and Genocide Studies. This summer, she is interning at Aegis Trust in Rwanda after spending the spring semester there studying post-genocide reconstruction and peacebuilding.

Thank you for a clear and informative article. Looking forward to a follow up in the months to come. For those interested about Burundi in the 90s, I recommend Gaël Faye’s novel “Small country”.