In June, there was a massive prison escape in the Congo, an accusation by Burundi’s government of the EU interfering with their regime, a vote in the US Senate on whether to block the Saudi arms deal, an increase in a cholera epidemic in Yemen, and an almost immediate outbreak of fighting after a peace deal attempt in the Central African Republic. More recently, Russia and the US negotiated a ceasefire in southern Syria, a decision was made not to refer South Africa to the UN Security Council for failing to arrest Sudan’s president Omar al-Bashir, a mob attacked Rohingya men in Burma, and South Sudan did not celebrate their independence due to the conflict.

Great Lakes of Africa

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

The Democratic Republic of Congo is close to falling back into civil war. Most state functions are near collapse. The court system has no budget, leading to judges charging additional money for services to make ends meet. This state failure stems from a lack of state authority in the country. Despite the fact that President Joseph Kabila’s second term finished in December, he has stayed in office. Citizens have consistently called for him step down and elections have been delayed. Hundreds have been killed in the last few months and more than a million people have fled since the conflict began in mid-2016, due to fighting between Congolese security forces and opposition militia. Roughly 400,000 children are at risk for severe malnutrition. A group of African leaders led by Kofi Annan stated in June, “We are deeply concerned about the political situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo [DRC], which represents a threat to the stability, prosperity and peace of the Great Lakes region and indeed for Africa as a whole.”

On June 11, armed men stormed Kangbayi prison in Eastern Congo, freeing over 900 inmates. Most of these inmates were convicted for their involvement in mass killings. The Congolese government has not identified the attackers, but sources claim that they are “Ugandan fighters of the Allied Democratic Forces, a rebel group that has been accused of killing more than 600 people in the past three years.” This is the fifth reported prison escape in the last month, totaling over 6,000. One Congolese citizen stated that these events show that the country is not well run and is “irresponsible,” questioning whether or not Kabila will use this as an excuse to delay the elections.

An election head in the country has said that an election for a new president will most likely not be logistically possible this year. This violates a deal permitting Kabila to stay in office past his term. The government claims they need more time to prepare for the election. Kabila’s term ended in December, but he has refused to step down, inciting violence in the country.

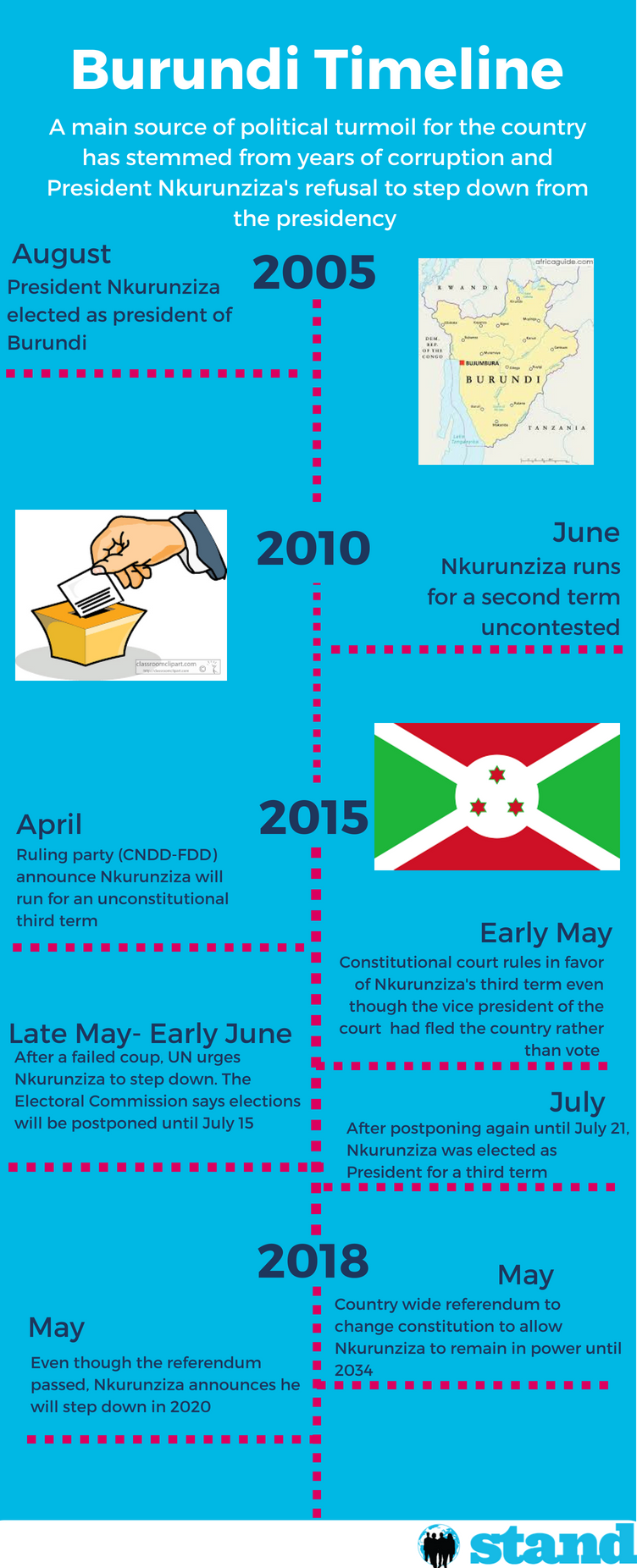

Burundi

The Burundian government has accused the EU of attempting regime change in Burundi, but the EU has denied these claims. Burundi claims to have obtained documents stating that the EU delegation in Burundi paid people who wanted to weaken and disrupt the country. The EU has been critical of President Pierre Nkurunziza’s government in the past but stated, “We formally refute these accusations. They are based on a deliberately wrong interpretation of a program of support for human rights defenders.”

According to a report from the Paris-based International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Tutsi officers are being removed from Burundi’s army. President Nkurunziza is a member of the majority Hutu group. Burundians fear that those who are being removed will form their own opposition group, sparking civil war. Burundi has experienced power struggles between the two groups since its independence in 1962, including mass killings and even genocide. Since the conflict began in mid-2015, it has been mostly political, but some have begun to worry that another genocide will occur in the country.

The refugee population from Burundi has grown dramatically in the last two years as the crisis continues. Thousands are fleeing to neighboring countries, with Tanzania hosting the most at 249,000 and the tens of thousands more being hosted in the DRC, Uganda, and Rwanda. It is expected that the refugee population from Burundi will grow to over half a million by the end of 2017, making Burundi the third biggest refugee situation in Africa. However, while the number of refugees is increasing, funds to help them are decreasing. A UNHCR spokesperson said that they have only received two percent of the $250 million they need to expand refugee camps and provide education to refugee children. Some host countries have reportedly returned refugees back to Burundi, which UNHCR is trying to prevent.

Middle East and North Africa

Yemen

Last month, the Senate voted on whether or not to block a $110 billion arms deal with Saudi Arabia. While the deal was not blocked, the number of Senators who voted for a block more than doubled since the last vote, demonstrating unprecedented opposition. The deal will have a critical impact on the crisis in Yemen, as Saudi Arabia has repeatedly targeted Yemeni citizens and infrastructure in Yemen through military action. The Saudi government claims to be using the weapons to defend themselves against Yemeni rebels, but, while all parties to the conflict have committed abuses against civilians, Saudi has been aided by U.S. and U.K. support.

The destruction of infrastructure has contributed to risk of famine, with about a quarter of Yemen’s population “one step away from famine.” Not only are many citizens suffering from severe malnutrition, but there has also been a recent outbreak of cholera, reportedly killing one person an hour, and 1,200 people to date. The UN blames the warring parties for this “man-made catastrophe.” Few medical facilities are still running in the country and about two-thirds of the population does not have access to safe drinking water, leading to the very high death rate, and in particular of women and children. There is a lack of medicine and intravenous fluids and most healthcare workers have not been paid in over nine months. The UN and other health organizations agreed on June 15 to send 1 million cholera vaccines to Yemen. Since then, however, they have decided not to pursue this plan due to the rapid spread of the disease. As a WHO statesperson stated, “The situation has evolved so rapidly that vaccines are not the priority tool to use right now.”

Syria

At the G20 Summit earlier this month, the US and Russia negotiated a ceasefire deal in southwest Syria. This ceasefire began on July 8 and is holding so far. The deal covers three war-torn provinces. There was some light fire between groups after the ceasefire went into effect, but officials said that this has not yet threatened the peace. There have been ceasefire attempts in the past and none have stayed, so tension in the area remains. Locals fear that while the ceasefire has been effective so far, there are not mechanisms in place to continue this progress. However, the ceasefire shows notable improvement in the conflict, as Russia and the US back opposing sides, with Russia supporting the Syrian government and the US advocating the removal of Bashar al-Assad. Yet Iran, the other major backer of the Syrian government, is calling for a ceasefire in all of Syria, not just specific regions.

Meanwhile, the UN held a new round of indirect talks between the Syrian government and opposition groups that began July 10 and lasted a week. This was the seventh attempt at reaching some sort of peace agreement since the civil war began. The opposition wants to focus the talks on a political transition, while the government thinks the focus should be on fighting terrorism in the country. The talks are reported to address both issues. The talks ended with some progress, but no breakthroughs. The UN plans to hold the next peace talks in September and hopes the groups will meet face-to-face for the first time.

Central and West Africa

Central African Republic (CAR)

A peace deal between 13 of 14 armed groups in CAR was signed a few weeks ago calling for an immediate ceasefire. However, just hours later, fighting began again. This was not the first peace attempt between the groups, as they signed peace deals in 2014 and 2015. The situation in the Central African Republic is very fragile and most parties believe a ceasefire is crucial.

After allegations of sexual abuse, 600 UN peacekeepers will be dismissed and returned to the Republic of Congo, their home country. There has also been an increase of attacks against peacekeepers in the Central African Republic. The UN envoy for CAR warned of these attacks as well as attacks on civilians. Violence has worsened in the past two months, with over 300 people killed in two weeks in May and six UN peacekeepers killed in one week in May. The international community has condemned the attacks.

CAR remains the most neglected crisis in the world, reports the Norwegian Refugee Council. The report found that the world pays the least attention when humanitarian crises force Africans from their homes, because this diminishes hopes of peace and raises the possibility of more conflict. The list of the ten most neglected countries includes the DRC, Sudan, South Sudan, Yemen, Nigeria, and Burma. This list was created by determining which countries lacked economic support to take care of basic human needs, had little media attention, and almost no political will to address the crises.

Sudan and South Sudan

Sudan

In 2015, Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir, who is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for genocide and crimes against humanity, traveled to South Africa for an African Union meeting, but the country failed to arrest him. The ICC criticized South Africa for this and rejected the argument that they did not arrest him because he was leading his country’s delegation and therefore was immune to arrest. A local court ruled that South Africa was required to arrest him, but by the time the decision had been made, he had already been approved to leave. However, even though the ICC strongly reprimanded South Africa, they decided on Thursday not to refer South Africa to the UN Security Council. Since his conviction in 2009, many other countries have also allowed him entrance without fear of arrest. This raises the concern that those convicted for genocide, war crimes, or crimes against humanity, will not be held accountable by the international community.

On July 12, President Trump decided to delay a decision on sanctions in Sudan. President Obama decided in January that Sudan was working on meeting requirements to lift sanctions and temporarily lifted them. He then tasked Trump with deciding whether to permanently remove them or reinforce them. This has raised a lot of debate as to which option will be more effective in promoting improvement in the country. Some argue that lifting them will prompt Sudan to be more willing to listen and make positive changes, but others argue that it will just allow the regime to continue committing human rights abuses against its citizens unabated. 53 members of Congress called on President Trump to delay the decision for a year. Notably, most senior staff positions in the U.S. State Department have not been filled, which is problematic because these staffers would likely be responsible for making the decision on Sudan sanctions.

South Sudan

For the second year in a row, South Sudan did not celebrate its independence day on July 9, because the government does not feel that it can spend money on a celebration when much of the country is living in extreme poverty and lacking basic human needs. Martha Athieng, whose husband and mother-in-law have both been killed since the fighting began, described the initial joy felt and celebrations held when South Sudan became independent. “We all hoped for a better life,” she remembers. “We never knew we’d start killing each other.” President Kiir called on opposition groups to respect the ceasefire and stop fighting.

South Sudan’s government has asked donors to fund more than one third of its new budget, because they do not have the resources to fully cover it. However, most countries are skeptical due to ongoing conflict and corruption. The country wants to avoid borrowing money from the central bank. Their oil production has been seriously harmed due to the conflict and in order to export, they must pay heavy fees to Sudan in order to use their infrastructure. The value of the pound in South Sudan has plummeted.

Millions of civilians are at risk of famine in the country and they now face a possible cholera epidemic. Similarly to Yemen, the country has few functioning medical facilities left and limited medications to help prevent the epidemic from spreading. About 8,000 have gotten sick in the last year and 250 have died, but experts believe this will only be a fraction of deaths that will occur from the disease.

Southeast Asia

Burma

One Rohingya man was killed and six were injured after a Buddhist mob attacked them with bricks on July 4. The Rohingya men were being escorted by police into Rakhine state’s capital from their displaced persons camp in order to buy boats. The mob attacked the men when they got into an argument with a Buddhist man over the price of a boat. The unarmed junior policeman who was accompanying them tried to help but was unable to and eventually fled. There is an investigation into the event, but no one has been arrested.

The UN is attempting to investigate the persecution and abuse of the Rohingya in Burma, but the Burmese government has said that it will not give the investigators visas to enter the country. The government has consistently denied that the Rohingya are facing discrimination and violence in the country or has stated that such reports are exaggerated. Aung San Suu Kyi, the de facto leader of the country, believes that an investigation will only increase ethnic tensions in the country. A UNHCR official, Fillipo Grandi, visited Burma for the first time at the beginning of July and urged the government to give the Rohingya people citizenship.

Three journalists were arrested on June 26 after covering a drug burning in the country. They were charged using a colonial era law. The drug burning was held by the TNLA, one of many ethnic minority armed groups in Burma fighting the government. This arrest raises concern about media freedom in the country.

–

Hannah King a rising junior at Clark University in Worcester, MA. She majors in Sociology with a minor in Political Science and a concentration in Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Hannah became involved in her STAND chapter this past year and is very excited to be interning with STAND in DC this summer!

Hannah King a rising junior at Clark University in Worcester, MA. She majors in Sociology with a minor in Political Science and a concentration in Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Hannah became involved in her STAND chapter this past year and is very excited to be interning with STAND in DC this summer!

The referendum took place on May 17, with months of escalating fear and violence in the lead up. The government issued threats to those who opposed the referendum, stating that they would arrest anyone who campaigned against it. The text of the referendum was not published until May 8, 9 days before the vote, and it was hidden deep within the National Independent Electoral Commission website. No link was publicized and it had to be “thoroughly searched to be found.” A recent briefing by the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi to the UN Human Rights Council detailed some of the violence and intimidation that occurred leading up to the referendum vote. Nkurunziza and his party made threats with “barely concealed incitements to hostility or violence.” Many who advocated against the referendum, asked to meet about the draft amendment, or refused to join the CNDD-FDD, were arrested and often tortured. Some opposition members were killed or abducted. Several remain missing and unidentified bodies continue to be found throughout Burundi.

The referendum took place on May 17, with months of escalating fear and violence in the lead up. The government issued threats to those who opposed the referendum, stating that they would arrest anyone who campaigned against it. The text of the referendum was not published until May 8, 9 days before the vote, and it was hidden deep within the National Independent Electoral Commission website. No link was publicized and it had to be “thoroughly searched to be found.” A recent briefing by the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi to the UN Human Rights Council detailed some of the violence and intimidation that occurred leading up to the referendum vote. Nkurunziza and his party made threats with “barely concealed incitements to hostility or violence.” Many who advocated against the referendum, asked to meet about the draft amendment, or refused to join the CNDD-FDD, were arrested and often tortured. Some opposition members were killed or abducted. Several remain missing and unidentified bodies continue to be found throughout Burundi.

Hannah King is STAND’s Campaigns Coordinator for the 2018-2019 school year. She is a rising senior at Clark University, where she studies Sociology, Political Science, and Holocaust and Genocide Studies. This summer, she is interning at Aegis Trust in Rwanda after spending the spring semester there studying post-genocide reconstruction and peacebuilding.

Hannah King is STAND’s Campaigns Coordinator for the 2018-2019 school year. She is a rising senior at Clark University, where she studies Sociology, Political Science, and Holocaust and Genocide Studies. This summer, she is interning at Aegis Trust in Rwanda after spending the spring semester there studying post-genocide reconstruction and peacebuilding.