This blog is the first in a series on the Global Fragility Act, signed into law on December 20, 2019, which would significantly reorient U.S. foriegn policy and assistance to address the root causes of violence. It requires extensive cooperation between U.S. diplomatic, development, and defence agencies in order to develop the Global Fragility Strategy (GFS), to be submitted to Congress on September 15, 2020. The GFS will be the first-ever whole-of-government plan to prevent or reduce conflict in at least five fragile contexts over a 10-year period. Under the new GFS, agencies will use a range of diplomatic and programmatic efforts to address the drivers of violence while the GFA will support learning. about which diplomatic and programmatic efforts are most effective at preventing and reducing violence. Learn more here.

“Our world faces a common enemy: COVID-19. The virus does not care about nationality or ethnicity, faction, or face; it attacks all relentlessly. Meanwhile, armed conflict rages on around the world. The most vulnerable, women and children, people with disabilities, the marginalized, and the displaced, pay the highest price. They are also at the highest risk of suffering devastating losses from COVID-19.” – United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres

On March 23, 2020, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres urged the international community to commit to a global ceasefire. All attention, he implored, should instead be turned to fight a shared enemy: COVID-19. Within days, governments participating in conflicts around the world began announcing that they would heed Guterres’ call for a ceasefire. Armed groups that have been fighting without stop for decades such as the New People’s Army (NPA) in the Philippines and the National Liberation Army (ELN) in Colombia put down their weapons. Even Saudi Arabia, a country responsible for indiscriminately bombing Yemeni markets, schools, and health care centers announced that they would adhere to a ceasefire in Yemen—albeit, a unilateral one. By early April, parties in an estimated 11 countries committed to a global ceasefire.

At first, the shared pandemic experience appeared to mitigate conflict, serving as a cause for cooperation. The Colombian and Venezuelan governments reopened communication for the first time in over a year to discuss how they could work together to fight the spread of the virus across their border. For the first time in over ten years, the U.S. sent aid to the Georgian region of Abkhazia. The United Arab Emirates—the main backers of the Saudis in Yemen—sent over 30 tons of humanitarian aid to Iran.

Yet, in Ukraine, where the fighting parties had verbally committed to the ceasefire, fighting continued as before. In other places, such as Yemen or Cameroon, ceasefires were either short-lived or ignored. In countries where ceasefires were agreed upon, they were mostly not renewed.

Now, months after Guterres’ call for a global ceasefire and the optimism of early March, the pandemic has proved that it is not, in itself, a path for peace. Indeed, there is no evidence global violence decreased in the past four months. Instead, conflict zones have seen the increased targeting of aid workers, massive displacement, and unabating outbreaks—factors only exacerbated by stanched aid flows and the international community’s reticence to take concrete and sustainable action to promote cooperation and prevention. On a broader level, a ceasefire does nothing to protect states classified as “fragile” who, being vulnerable to shocks like health crises, are among the most susceptible to future conflict.

The international community has had ample opportunity to learn how conflict and disease act like fuel and flint, feeding into each other’s worst effects. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where conflict has raged on for nearly three decades, fractionalization of power and the devastation of infrastructure has rendered health care and aid practically inaccessible. As such, thousands of Congolese lives have been lost in the country’s ten-plus major outbreaks of Ebola. In Yemen, the Saudi-led coalition’s blockade and airstrikes have destroyed water sources, razed hospitals and clinics, and manufactured a man-made famine—factors credited with generating “the largest cholera outbreak in epidemiological recorded history.”

One clear lesson is that mass displacement invites outbreak among conflicts’ most vulnerable: displaced persons and refugees. Since late March, approximately 480,000 people have been displaced due to violence in the Congo—a region that must simultaneously battle Ebola, conflict, and now COVID-19. Similarly, in refugee camps, cramped and unhygienic conditions make following World Health Organization guidelines like “social distancing” a laughable impossibility. Perhaps most worrying, because conflict zones render conducting and processing testing difficult, we cannot yet quantify COVID-19 infections in conflict-affected regions. When surveyed in mid-April, around one-fourth of Rohingya refugees in camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh reported experiencing at least one common symptom of COVID-19.

Even in places where WHO guidelines could theoretically be enforced, COVID-19 has proved to be a trust exercise between governments and the governed—meaning that in conflict zones where authority is ambiguous or viewed as unjustified, people are less likely to adhere to safety guidelines due to a lack of trust. Many of the same states that struggle with citizen-state trust internally are likely underreporting their COVID numbers internationally. Many suspect that the Burundi president’s recent death—supposedly from cardiac arrest—was the result of COVID-19. After the government vehemently refused to impose health and safety regulations, the president’s sudden death by illness suggests that the disease had a much further reach than the government has reported. Similarly, Yemen currently touts incredibly low COVID-19 numbers compared to its Middle East neighbors. This is most likely not a sign that the warzone has miraculously been spared; as of May 28, authorities had conducted less than 1,000 tests across the entire country. Reports abound of hospitals and health care centers turning away people with symptoms common to COVID-19.

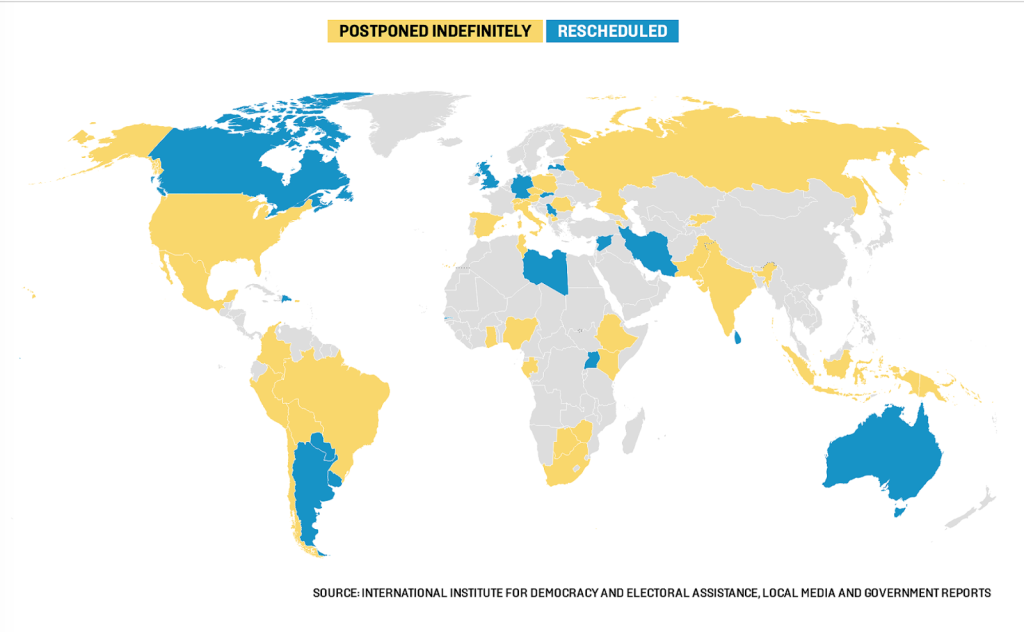

While the concept of trust allows us to understand how conflict has shaped the pandemic experience, it, perhaps more importantly, suggests how the pandemic experience might shape future conflict. COVID-19 has already caused extensive individual health, social, and economic damage. We cannot predict its trajectory. This latter fact presents more troubling uncertainties. We can only hypothesize the extent of the consequences that this disease will have on the world order, the shape of our societies, or even the health of those it infects. Already, governments like Russia have been curtailing human rights in the name of preventing COVID-19. Across the world, major elections have been rescheduled or delayed indefinitely. Especially in states with broad emergency powers, this opens up opportunities for unpopular or exploitative governments to stay in power.

How many will die or be displaced not by COVID-19, but by the world’s response to it? On the Venezuela/Colombia border, a bridge closed, diverting the estimated 35,000 Venezuelan refugees who used it daily to dangerous illegal crossing points. The world’s response has already triggered a global recession with profound effects: according to a USIP report, “nearly half of all jobs [in Africa] could be lost, and nearly half of the global population could be living in poverty—on less than $1.90 a day—as a result of the pandemic.”

Not since the Spanish Flu have we seen a pandemic that has so ravaged the global economy, interrupting flows of aid and sowing the seeds for future conflicts. Just in time for a swelling need, foreign aid workers have been airlifted out of conflict zones—both due to safety and the evaporation of funding. Those who remain on the ground face overwhelming hurdles to receive aid and make it accessible while still maintaining their own lives as funding dries out and the pandemic rages on.

If there is one lesson that we learned in the 20th century, it is that it is far cheaper to prevent conflict than to mitigate it. In light of dwindling funding and growing need for aid, the United States has an unprecedented chance to implement the Global Fragility Act to counter some of the effects of the pandemic on the world’s most fragile states. Since the bill passed as a part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act in December 2019, its funding can work against the global downward capital flows of the COVID-19 pandemic today and continue to provide a stable foundation of aid in target regions in the years to come.

Abby Edwards is STAND’s co-Student Director and a senior in the Dual BA program between Sciences Po Paris and Columbia University, where she is pursuing degrees in Human Rights and Politics & Government. In addition to her work with STAND, Abby is currently a research fellow with the Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University and an intern at the Embassy of France in the United States.