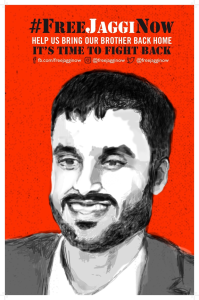

In broad daylight on November 4, 2017, Jagtar Singh Johal, a British Sikh man, was abducted from the streets of Jalandhar, Punjab in India by police officers in plain clothes. He was subjected to abuse, ranging from body separation techniques to electric shocks, in order to extract a confession of involvement in the murders of prominent Hindu figures – crimes he did not commit. He was initially denied access to British consular officials, his family, or a lawyer. He became a man in the midst of oblivion for ten days after his arrest, not permitted to speak to his family, including his newly-wedded wife. Johal is a simple man with a passion for uncovering the truth and advocating for justice. He runs a website called Never Forget 84 , which strives to highlight the 1984 Sikh Genocide and injustices faced by Sikhs in modern-day Punjab. Simply because he advocated for human rights, for justice, and against genocide, the police force tried to break him down through excruciating physical pain and wrenching mental torture- a pattern seen throughout the history of independent India. Alone and hidden away from the outside world, his existence could too easily have been forgotten if not for the brave activists of #FreeJaggiNow.

Johal was vacationing in India after his wedding when he was arrested under the pretense that he was involved in targeted killings of minority leaders and funding the Khalistan Liberation Force, an armed group dedicated to creating a separatist state. The Sikh Federation UK, an organization that raises awareness about Sikh issues, suggests that Johal was targeted because he is a human rights activist who detailed the atrocities of the Indian state during the 1984 Sikh Genocide on a website called Never Forget 1984. Senior Punjab Police officials maintain that he was “neck-deep” in targeted killings and also express concern about Johal’s activism and his influence on youth, calling it radicalization, a tactic long used by oppressive regimes as an excuse for extra-judicial action.

Johal was vacationing in India after his wedding when he was arrested under the pretense that he was involved in targeted killings of minority leaders and funding the Khalistan Liberation Force, an armed group dedicated to creating a separatist state. The Sikh Federation UK, an organization that raises awareness about Sikh issues, suggests that Johal was targeted because he is a human rights activist who detailed the atrocities of the Indian state during the 1984 Sikh Genocide on a website called Never Forget 1984. Senior Punjab Police officials maintain that he was “neck-deep” in targeted killings and also express concern about Johal’s activism and his influence on youth, calling it radicalization, a tactic long used by oppressive regimes as an excuse for extra-judicial action.

Johal is still under custody and his lawyer, Jaspal Singh Manjhpur, meets with him for an hour every day. His request for an independent medical board was denie d because it would be too late to find physical signs of torture or the effects of severe medical torture, Manjhpur has since decided not to press for an examination. Manjhanpur has also expressed concern that no formal charge has been named and that his court date keeps getting postponed, thus extending his stay in police custody.

d because it would be too late to find physical signs of torture or the effects of severe medical torture, Manjhpur has since decided not to press for an examination. Manjhanpur has also expressed concern that no formal charge has been named and that his court date keeps getting postponed, thus extending his stay in police custody.

The Sikh diaspora in the United Kingdom and the United States have raised their voices through social media and protests, starting a campaign called #FreeJaggiNow. A petition for Johal’s release has almost hit its 50,000 signature goal. The social media campaign has also gained significant momentum with multiple individuals conducting street parchar (educating pedestrians) in the UK and many gurudwaras (Sikh houses of worship), have held prayers and educational events. A gurudwara in San Jose recently brought together Bay Area universities in order to host a kirtan (a melodic recitation of the verses in the Guru Granth Sahib) night for Johal, and many other student groups and communities are following suit.

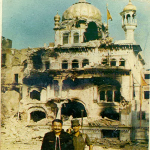

The Johal case has brought the 1984 Sikh Genocide and subsequent killings, illegal arrests, and discrimination against Sikhs to the forefront of conversation once again. Johal’s activism has reawakened the narrative of Sikh suffering, and continued human rights abuses against Sikhs by the Indian state. Recent legislative acts have darkened the Sikh population, and include t he National Security Act of 1980, the Terrorist Affected Areas Act of 1984, the Armed Forces Special Powers Acts of 1983, and the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) of 1985. Since independence in 1947, these pieces of legislation have given extra-judicial powers to the police, inciting a trend of false cases and mass incarcerations of wrongfully accused activists and innocent Sikh men. In 1955, security officials killed 200 Sikhs and illegally detained over 12,000 in an attack at Harmandir Sahib, the main house of worship for Sikhs in Amritsar, Punjab. In 1984, Harmandir Sahib was attacked again by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. This attack, known as Operation Blue Star, killed 70 innocent pilgrims, and around 40 bodies were found.

he National Security Act of 1980, the Terrorist Affected Areas Act of 1984, the Armed Forces Special Powers Acts of 1983, and the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) of 1985. Since independence in 1947, these pieces of legislation have given extra-judicial powers to the police, inciting a trend of false cases and mass incarcerations of wrongfully accused activists and innocent Sikh men. In 1955, security officials killed 200 Sikhs and illegally detained over 12,000 in an attack at Harmandir Sahib, the main house of worship for Sikhs in Amritsar, Punjab. In 1984, Harmandir Sahib was attacked again by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. This attack, known as Operation Blue Star, killed 70 innocent pilgrims, and around 40 bodies were found.

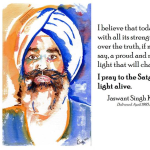

This oppre ssion and continued denial of genocide and human rights abuses did not end in the 1980s, and Sikh political prisoners are still held, without trial, under false allegations. In 1995, human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra, known as a martyr of Sikhism for his justice work on missing and killed Sikhs, was also arrested for revealing ledgers documenting the firewood used for the mass cremations of Sikhs during the decade following the genocide. He was only able to investigate one of the 13 districts of Punjab, but even within this one district documented the mysterious disappearance of 25,000 Sikh youths. Khalra was killed while in police custody, and although witnesses have implicated the police, the chief at the time, Kanwar Pal Singh Gill, was never held responsible for the crime. Over 10 years later, six minor police officials were finally convicted; however, the main conspirators and human rights abusers escaped without any implications. The lack of justice for those that commit mass state crimes against Sikhs is evident in the way the Indian government continue to glorify perpetrators through posthumous memorials, appointments, or reinstatements of Indian off

ssion and continued denial of genocide and human rights abuses did not end in the 1980s, and Sikh political prisoners are still held, without trial, under false allegations. In 1995, human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra, known as a martyr of Sikhism for his justice work on missing and killed Sikhs, was also arrested for revealing ledgers documenting the firewood used for the mass cremations of Sikhs during the decade following the genocide. He was only able to investigate one of the 13 districts of Punjab, but even within this one district documented the mysterious disappearance of 25,000 Sikh youths. Khalra was killed while in police custody, and although witnesses have implicated the police, the chief at the time, Kanwar Pal Singh Gill, was never held responsible for the crime. Over 10 years later, six minor police officials were finally convicted; however, the main conspirators and human rights abusers escaped without any implications. The lack of justice for those that commit mass state crimes against Sikhs is evident in the way the Indian government continue to glorify perpetrators through posthumous memorials, appointments, or reinstatements of Indian off

icials.

Without fair trials and condemnation of genocide perpetrators, the Sikh community will continue to face oppression by the Indian state, and Jagtar Singh Johal’s murder will become one of many examples of this horrific cycle. Johal cannot be forgotten or become another statistic. As activists and believers in justice, we must raise our voices for his release and condemn the use of physical and mental torture against both Johal and all human rights advocates. As Johal did, we must come together as community to raise awareness about the Indian government-sponsored human rights abuses and continued oppression of Sikhs. We must work with the Sikh diaspora and the sympathetic Indian citizens to stop discrimination against Sikhs and create space for justice in India.

Here are some things you can do right now:

- Sign the “Justice for Jagtar Singh Johal” and “Condemn India’s Denial of Justice to the Victims of November 1984 Sikh Genocide.” petitions to show your support.

–

Harleen Kaur is a freshman at Stanford University, studying International Relations on a pre-medical track. She has been a part of STAND for five years and is the Field Organizer for high school chapters this year. Her family comes from Punjab and can recall the horrors of the 1984 Sikh Genocide. This family history has inspired her to study human rights and raise awareness about genocide prevention.