Burundi is another Rwanda, but not for the reason you think.

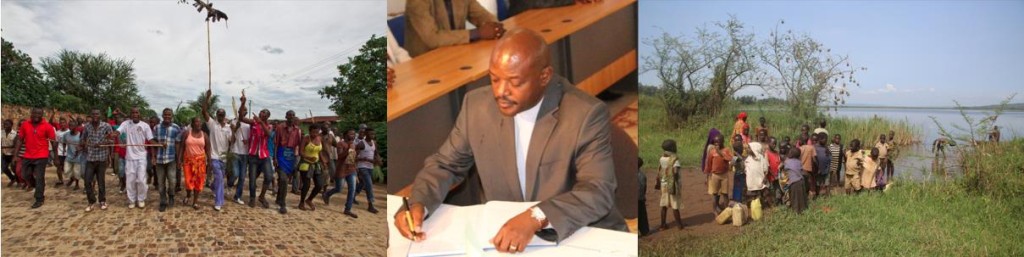

From left to right: Political protests against Nkurunziza’s 3rd term; Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza; Burundian refugees fleeing to neighboring Rwanda in fear of escalating violence and political targeting

In recent weeks, western media has been preoccupied with the refugee crisis, the terrorist attacks in Paris, and the ever-imminent threat of terrorism. Growing fear of foreign refugees has sparked a comparison to the world’s attitude towards Jewish refugees during World War II. Presidential candidates Donald Trump’s call for Muslims to bear religious badges harkens back to Germany in 1939. This is not the only crisis resembling darker times in our collective history. The rise in violence and hate rhetoric in the small East African nation of Burundi is an alarming reminder of the shared inaction of the international community during the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

The violence in Burundi began in April when sitting President Pierre Nkurunziza announced he would pursue an unconstitutional third term. Nkurunziza won the July elections by a large margin, prompting several international leaders, such as the US Secretary of State John Kerry, to question the democratic legitimacy of the elections. Violence between Nkurunziza’s party and the political opposition has intensified in subsequent months. There has been targeted political silencing and violence against civilians. As of last weekend, over 250 civilians have been killed and more than 200,000 have fled to neighboring countries.

Burundi’s complex problems are rooted in the region’s history of colonial oppression, big-man politics, and regional violence. The country last experienced widespread violence in 2003-2005 when an estimated 300,000 people were killed. Given the circumstances, it may be tempting to cast the current violence as genocidal, akin to the Holocaust of the Rwandan genocide. But while crying genocide in the face of ethnic or political violence in Africa is an easy answer, it is not the right one. Instead, Burundi speaks to a recurring theme of international inaction in the face of “unworthy” or “insignificant” conflicts.

Rather than genocide, Nkurunziza regime’s violence towards civilians is the systematic violence of subjugation. If civilians are being murdered, some might ask, do definitional semantics really matter? Yes, they do. According to the 1948 Convention on the Prevention of Genocide; genocide is the systematic and intentional destruction of a racial, religious, ethnic, or national group. The word was invented by a Jewish man in 1945 in response to Nazi war crimes. The word is meant to alert international actors to one of the most destructive forms of violence. As such, the word “genocide” should only be used as a final resort. When used incorrectly, it loses its severity and meaning. In assessing violence, definitions are incredibly important so we know the possible trajectory and the appropriate forms of response.

The current conflict in Burundi is violence of subjugation. Jacques Sémelin, a genocide scholar at Science Politiques, states that subjugation occurs when an actor “annihilate[s] a group partly in order to force the rest into total submission.” When constitutional term limits threatened Nkurunziza’s position of power, the president initiated a campaign of violence designed to secure his power through fear. His primary focus is power, not the intentional and complete destruction of his citizens. Nkurunziza’s pointed use of rhetoric from the Rwandan genocide is another powerful and telling step in the subjugation. These threats are an incredibly effective tool of subjugation since many Burundians were affected by the Rwandan genocide. Citizens fall obediently silent because they fear the language used.

As civilians suffer in Burundi, the world must decide how to respond. We must develop and sustain international concern for the ongoing violence in Burundi. Should this violence escalate, history shows the United States will likely be involved in a peacekeeping and humanitarian capacity. The political and economic costs will be enormous if we wait until the bodies have been buried. Inaction sends a message to an increasingly unstable region that indiscriminate violence towards civilians will be tolerated. This breeds a culture of impunity and instability. From a more pragmatic perspective, it is incredibly expensive to rebuild democracy and stability following violence against a civilian population.

Although the UN recently signed a resolution condemning the violence, more than 500 Belgian nationals were asked to leave the country last week. The world is collectively turning away from Burundi during a time in which civilian security is dependent on international action. Inaction in the face of Nkurunziza’s violent regime is the worst possible response.

This crisis demands international attention. Burundi needs NGOs documenting violence on the ground, diplomatic negotiations with the Nkurunziza regime, and the focus, care, and political pressure of millions of individuals. Boots on the ground is not the solution, but silence is the worst thing we can offer the people of Burundi. Bystander-ship allows room for further violence. Should this situation escalate further without concerted international efforts to stop it, Burundi will be remembered as another flagrant instance of inaction in the face of brutal atrocities.

—

Corie Walsh is a senior at the University of North Carolina, studying Peace, War, and Defense, and researching genocide, civilian protection, and identity-driven conflict. Notably, Corie co-founded a micro-finance program for Ugandan women; started the first collegiate chapter of the UN Shot@Life Campaign; and has engaged in initiatives such as AIESEC, RESULTS, Roosevelt Institute, Conference on World Affairs, and Beyond Conflict. Corie blogs at Nomadic Tendencies and can be reached at coriewalsh@gmail.com.

Corie Walsh is a senior at the University of North Carolina, studying Peace, War, and Defense, and researching genocide, civilian protection, and identity-driven conflict. Notably, Corie co-founded a micro-finance program for Ugandan women; started the first collegiate chapter of the UN Shot@Life Campaign; and has engaged in initiatives such as AIESEC, RESULTS, Roosevelt Institute, Conference on World Affairs, and Beyond Conflict. Corie blogs at Nomadic Tendencies and can be reached at coriewalsh@gmail.com.

Savannah Wooten serves on the Managing Committee of STAND as the Mid-Atlantic Regional Organizer. She is majoring in Public Policy and Peace, War, and Defense at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University through the Robertson Scholars Leadership Program. Savannah has engaged in comparative human rights coursework and research in Chile, Jordan, Nepal, and Rwanda, where she has studied a variety of pressing human rights and conflict-related subjects. Savannah can be reached at swooten@standnow.org.

Savannah Wooten serves on the Managing Committee of STAND as the Mid-Atlantic Regional Organizer. She is majoring in Public Policy and Peace, War, and Defense at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University through the Robertson Scholars Leadership Program. Savannah has engaged in comparative human rights coursework and research in Chile, Jordan, Nepal, and Rwanda, where she has studied a variety of pressing human rights and conflict-related subjects. Savannah can be reached at swooten@standnow.org.

I believe you mean 1993-2005, not 2003-2005. Those are the years of the most recent Burundian war, which began when Melchior Ndadaye, the first democratically elected president and the first Hutu president, was assassinated by the predominantly Tutsi army.