I was fifteen when I was told I was not “Jewish enough” for the first time. I went on a two week Jewish youth trip to Poland and Israel. The week in Poland was spent visiting eight concentration and death camps in a matter of seven days. My peers were mostly devout, orthodox and conservative Jews, whereas I had been raised in a muddled Catholic and Jewish home without any clear religious direction. Nonetheless, I was thrilled to finally be surrounded by my Jewish peers and hopefully find a connection to what felt like a long lost religion.

Each night in Poland, we had group sessions with our chaperones. We discussed our experiences and our emotions and tried to process what we had seen. One night, after visiting a particularly challenging camp, we were gathered in the circle. As the youngest and least devout person on the trip, I worried that they would discover I was in fact an imposter. One of the girls raised her hand and, as she described her experience from that day, she remarked, “I’m glad we’re all Jewish. I don’t think you can understand the Holocaust the same way unless you are.”

A swift wave of anger, unique to teenagers, came over me. I raised my hand and waited for my turn to speak my mind. Perhaps I was looking for a reason to be indignant, to prove to myself that I was an outsider, to have somewhere to channel my anger after days of looking at mass graves. Whatever it was, as soon as the chaperone called on me, I lost my grace.

“Not Jewish enough?” I cried. “Not Jewish enough? Do you know my father is Catholic? Do you know I was never Bat Mitzvah’d? Do you know I don’t go to temple? Do you really want to tell me I understand this less than you? Really?”

By the end, my voice was loud and cracked, straining for composure. I felt dozens of eyes staring back at me and I felt terribly unwelcome.

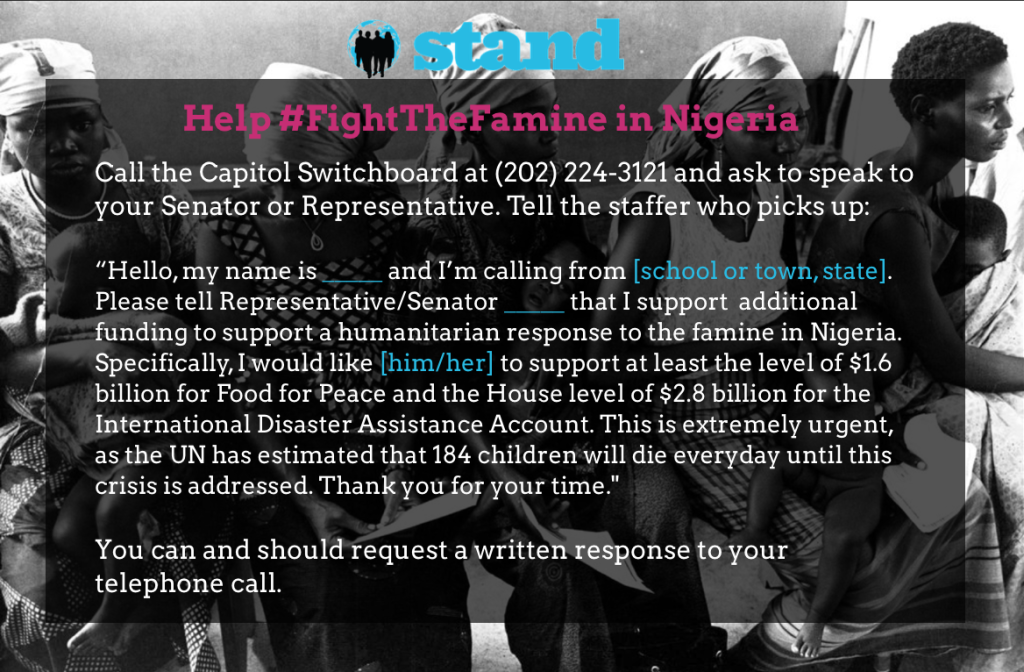

Remembrance Pavilion at Srebrenica (Source: Wikimedia)

It’s hard to mourn when you feel like an outsider. The trajectory of that evening was in part the fault of the young woman’s perception of emotional inclusion and in part due to my rash reaction — either way, for the rest of the trip, I never felt Jewish enough. I was trying to simultaneously process the images from Majdanek, Chelmno, Sobibor, Plaszow, Auschwitz, Birkenau, Treblinka, and Belzec and also understand why I felt inherently unaccepted by my people.

It took me weeks and then years to begin to process my place in my religion. My first point of clarity came while walking through Auschwitz with Barbara, a gentile woman in her 70s from Connecticut, who had accompanied her friend Judy, a Holocaust survivor on the trip. She was Judy’s moral support as she revisited the places where her mother, father, sister, and nieces had been killed. But when Barbara was away from Judy, her pain was undeniable. We were walking through one of the barracks in Auschwitz and she grasped my hand and pleaded, “Corie, why would humans do this to each other?”

In the subsequent years, my moments of clarity have been built around remembering atrocities. In Bosnia at Srebrenica, a Muslim-Bosniak widow grabbed my hand and thanked me for coming to visit their dead. In Rwanda, my cab driver (turned friend) and I walked arm in arm as we entered a church where 11,000 families had been killed. In Prague, at the oldest standing Synagogue in Eastern Europe, I stood with my Christian friend and we imagined if we ever would have met as Jews and Christians in a WWII Europe. In Cambodia, at the main torture facility, I held hands with one of the 15 men to survive the facility, and in broken languages, we thanked one another for showing up.

Remembrance Pavilion Tuol Sleng (Source: Corie Walsh)

Genocide remembrance has never been and will never be about being part of a culture. It signifies our shared humanity, our ability to transcend our groups and communities and instead choose a common empathy. Remembrance and commemoration in its purest forms is about seeing someone else’s pain, seeing what they have lost, and saying, “Give me a piece of your burden. I will carry it with you.” Our communities and traditions are sacred to the foundations of our values and practices, but once they become exclusionary, they become dangerous.

Remembrance and commemoration in its purest forms is about seeing someone else’s pain, seeing what they have lost, and saying, “Give me a piece of your burden. I will carry it with you.”

This is the unique eloquence and beauty of Together We Remember. There is strength in sharing remembrance and memorialization. Collective memory creates resilience. It is not meant as a competition of who suffered more, but instead a mutual commemoration of our persistence. Genocide is one of the most brutal crimes. It is the intentional destruction of a group based on inalienable aspects of their identity. If successful, it eliminates the presence and history of a people. But together we can defy that and together we can remember the mutual suffering of victims of genocide.

I learned a long time ago that for many I am not Jewish enough. But in visiting over twenty-five different genocide and memorial sites, I learned that I am human enough and I carry the capacity for empathy — regardless of whether or not I am a member of the group — and that’s enough for me.

–

Corie Walsh works at the humanitarian organization Mercy Corps and spends her free time writing, cooking, and trying to do a little good in the world.

This post originally appeared on Medium for Together We Remember.