This blog is the second in a series on the Global Fragility Act, signed into law on December 20, 2019, which would significantly reorient U.S. foriegn policy and assistance to address the root causes of violence. It requires extensive cooperation between U.S. diplomatic, development, and defence agencies in order to develop the Global Fragility Strategy (GFS), to be submitted to Congress on September 15, 2020. The GFS will be the first-ever whole-of-government plan to prevent or reduce conflict in at least five fragile contexts over a 10-year period. Under the new GFS, agencies will use a range of diplomatic and programmatic efforts to address the drivers of violence while the GFA will support learning. about which diplomatic and programmatic efforts are most effective at preventing and reducing violence. Learn more here.

In 2009, the United Nations Secretary-General set a precedent for incorporating local organizations in peacebuilding efforts. The report on Peacebuilding in the Immediate Aftermath of Conflict states, “We know that peacebuilding is a national challenge and responsibility. Only national actors can address their society’s needs and goals in a sustainable way.” The report goes on to detail key aspects that lead to continued fragilities. Some argue that international peacebuilding efforts reinforce global priorities, rather than the needs of the community.

This reflects the traditional top-down approach to peacebuilding. Because international organizations have their own operational procedures and bylaws, their peacebuilding efforts abroad reflect external systems. In a Washington Post article, an NGO worker in Congo is quoted stating, “There is so much pressure to be accountable… complying with the rules and regulations and not having any corruption or fraud. There is not much appetite for failure. You often have problems because you don’t have time to train people. We don’t even have any reflection time. If an activity is not a big failure, we just go onto the next thing.” The need to spend allocated funds is another problematic component of top-down peacebuilding. International organizations typically focus on spending their allocated money, rather than addressing the needs of a community. An international staff member from South Sudan mentions, “People spend 40 percent of their time talking about their burn rate [the rate at which they spend allocated funds].” However, to ensure a more peaceful transition and prevention of future conflict, peacebuilding efforts must become a bottom-up approach, including the perspective of civil society and marginalized groups.

In conversations about a bottom-up approach to peacebuilding, the term “local” gets used a lot. However, the international community struggles to agree on a definition of the term. In workshops hosted by the United Nations University Institute for Sustainability and Peace in 2009 and 2010, participants did not come to a clear consensus on what determines a local stakeholder. “Locals” can mean government representatives, civil society groups, community and religious leaders, and marginalized groups, such as women, children, and minorities from the conflict-affected area.

Even though the United Nations and other prominent international organizations praise the concept of locally-led peace initiatives, they do not always follow their own advice. International peace programs are crucial for facilitating peace agreements, maintaining peace between parties, and providing financial and technical resources. However, these interventions only help the short-term impacts of violence and do not address the root causes. A report by Peace Direct and the Alliance for Peacebuilding argues, “Peace is only sustainable when it is driven and led locally, that is, by the people and institutions of the country or countries concerned. This is because peace is only likely to be sustained when local people take the lead. They know the context well enough to judge what measures might work, and have the knowledge, relationships, and motivation needed to ensure they do work, especially over the longer term.” When developing and implementing strategies related to international peacebuilding, the perspective and action of local communities are necessary for successful implementation. They are the only people who truly understand how the conflict impacts their diverse community members. They can also respond to new developments and changes in the conflict. Thus, when developing a plan for peace, international organizations and other states must practice what they preach and be a guide rather than an administrator or sole leader.

Peace Direct makes it easy to connect with local peacebuilders and local experts on the conflict in the country or region. They developed PeaceInsight, a map that organizes over 1500 local peacebuilding organizations around the world. Peace Direct recognizes that local peace leaders are often forgotten, even though they have the most impact on preventing and resolving conflict in their communities. This map aims to bring awareness and public support to local peacebuilding efforts. By simply clicking on a country of interest, a user can find a list of local organizations, read blogs on the conflict, and connect to a local peace expert.

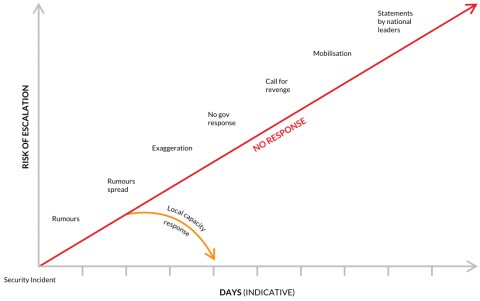

Local peacebuilding has been proven effective. In Burundi, communities that established ‘peace clubs’ saw a significant decrease in electoral violence between 2010 and 2015. The Democratic Republic of Congo also saw a reduction in violence after peace committees facilitated dialogue with armed militia groups. Communities in Kordofan, Sudan established peace committees as well. In their evaluative studies, they discovered 94% of interventions partially or fully resolved the conflict, and 80% of interventions where conflict ended saw no further violence. Sierra Leone’s Fambul Tok programme evaluations showed that 84% of people believed that the program prevented conflict, as well as 96% of the respondents saw containment of violence. The graph below demonstrates the importance of early local response and the potential consequences if not addressed locally. These statistics and examples taken together exemplify the importance of locally-led peace initiatives.

Credit: Christian Aid, ‘In It For the Long Haul?: Lessons on Peacebuilding in South Sudan’, 2018.

The future implementation of U.S. foreign policy must include locally-led and owned peace initiatives. December 2019 marked a significant date in U.S. foreign policy’s recognition of the importance of local peacebuilding. With the signing of the Global Fragility Act, coordination with local organizations to carry out the conflict prevention policy in selected priority regions became mandatory. In approximately one month, the President must submit a Global Fragility Strategy (GFS) to Congress. The law mentions multiple points that focus on locally-led peacebuilding, such as empowering local leaders to understand the needs of their communities and developing, designing, implementing, and monitoring peacebuilding programs that address root causes to fragility and violence in their communities. These points must not be perfunctory in developing the GFS.

Last month, Peace Direct and the Alliance for Peacebuilding published a report on the intersection of the GFA and local peacebuilding after co-hosting a virtual dialogue with 140 participants from 39 countries. Through these talks, they found that conversation with all groups of local peacebuilders is essential for an effective GFS and comprehensive understanding of violence. Peacebuilders expressed the need for inclusion throughout the entire process from designing, implementing, and evaluating programs. Participant Dlanga Yusuf of Nigeria states, “To overcome challenges to local participation, we need to prioritize the bottom-top approach of our project design and implementation. Participation in project design, promote owner[ship], and community engagement.” The participants express how the U.S. government and organizations should relinquish their extensive involvement in conflict analysis and program development and implementation. Participant Reem Alsalem from Jordan states, “Involving civil society organizations and grassroots organizations that are truly connected to the communities and that understand the context and the needs is key.” Something participants recommend is that the U.S. should provide funding for trauma, psychosocial, and mental health resources. In response to all of these findings from the conversation, Peace Direct recommends that the GFS and GFA implementation engages the entirety of the local community, includes and prioritizes local perspectives, and addresses barriers to local engagement early.

The GFS must bridge the gap between policy rhetoric and the reality of what happens on the ground. For the GFA to be effective, local peacebuilders must lead and take ownership of the efforts in their community. This act presents the opportunity for the United States to be a part of long-lasting change in global conflict reduction and prevention by allocating the funds and providing resources and support, but ultimately leaving the development, implementation, and evaluation of peace efforts to the locals, the first-hand experts of their lived experiences with conflict.

Jenna holds a Bachelor of Arts in Global Studies from Bridgewater College. She is currently working towards two Master of Arts degrees at West Chester University of Pennsylvania: Holocaust and Genocide Studies and General Psychology. The guiding theme of Jenna’s research is the overlap of social/peace psychology and mass atrocities. She is specifically interested bystander and rescuer behavior during genocides. In addition to her extensive research in genocide studies, she has a background in advocacy. As a member of the Church of the Brethren, she attended three Christian Citizenship Seminars lobbying for policies related to carbon footprint, childhood poverty, and immigration. She also held an internship at the Borgen Project where she wrote articles connecting global poverty and human rights abuses, lobbied congresspeople, and fundraised for the organization.